Andriesen Marries UZR

Dave Andriesen writes a piece about the Mariners outfield defense and… well, just read it.

Gutierrez played 134 games last season for Cleveland, the highest total of his career. And according to a statistic called ultimate zone rating (UZR), meant to place a hard value on a player’s defense, Gutierrez was the second-most valuable outfielder in baseball.

UZR uses a variety of factors to determine the number of runs, compared with the average player at his position, a player theoretically saved his team. Gutierrez had a UZR of 21.7. That would mean Gutierrez personally cost Indians opponents about a run a week more than an average fielder would.

To put it in simpler terms, the guy knows what he’s doing out there.

And even if the loss of Raul Ibanez creates a challenge on offense, better outfield defense can make up for it. The Mariners last season had a team outfield UZR of minus-16.8, meaning they surrendered that many extra runs because of below-average defensive ability. The league-leading Rays, meanwhile, had a UZR of 47.1. That’s a spread of almost 64 runs saved, which is just as valuable on the scoreboard as 64 runs created.

“That’s what we talked about during the winter — can we get better defensively?” Wakamatsu said. “Knowing that we lost somebody like Raul, can we gain some leverage on (the defensive) side of it?

Hooray for Dave Andriesen.

Jarrod thinks you live in your parents’ basement

From the Times

Washburn is aware there’s a segment of Mariners faithful less than enamored with him.

“Nobody ever says it to my face,” he said. “I think most of those people who do that … they hide behind their computer and write it online and do all that and nobody ever knows who’s saying it. Lots of people can do that.”

I’ve really tried to keep my dislike for Jarrod limited to the things I don’t like: the Johjima stuff, specific comments, and so on. But this just begs for a response.

Jarrod, maybe they say it to your face but you don’t understand them because they’re speaking Japanese. Right now in Japan there might be people doing press interviews about your poor communication skills.

Or maybe they’re afraid you’re going to shoot them and have the kill scored.

And I don’t know about most people — that’s probably true, the Internet is a wonder of anonymity with all the joy and horror that entails. But I put my name on the site and every post, and so does Dave, and so do the Lookout Landing guys.

I’ll just get this over with, though. Hey, Jarrod’s face from MLB.com?

“Huh?”

You weren’t that great last year, and that business with trying to publicly blame Johjima for your poor performances was low. Whether or not you feel that way, you should have kept it out of the press.

“Huh.”

“Was I overpaid last year? Yeah, for what I did,” he said. “But somebody told me once that when you sign a contract like that, you’re not pitching for that contract. You’re getting paid now for what you did in the past — when you weren’t making any money and [were] putting up the numbers.”

This is entirely fair, and I don’t ever blame players for getting paid as much as they can. I don’t know that Washburn’s getting paid for what he did in the past, but that’s a whole other argument. Blame the guys who offered him the deal, not him for signing it.

But the way this is worded is bad. It’s really bad. You’re being paid to pitch, and even if we buy the assumption that the money is based on the past performance, this seems to let anyone off the hook for any post-signing performance. If you’re the highest paid free agent pitcher and you don’t do any conditioning work and suck all season, that’d be fine too, because you’re being paid for what you did when you cared, right….? Down that path lies madness.

I don’t think if you put the question to Washburn that way that he’d agree, either — I suspect this is just a case of not quite saying what he thinks, if you will, or not entirely seeing how it would come across.

And at least he’s being honest, and we know he hates people on the Internet now. Would we rather he said that or “Fans who come out to see a game expect a good performance, and too often I failed to deliver that. I understand their frustration and look forward to this new season when I can prove…” ? I don’t know that I would.

Griffey And The Outfield

(Warning – this post is pretty ridiculously long.)

Okay, so we’ve had the press conference, the first workout, the chemistry/leadership talks, the relationship with Ichiro, and all the related welcome back stories. Now, back to what we do best – talking about the on field issues of the team and finding positions that are supported by evidence.

The topic for today – in what situations should Ken Griffey Jr play left field for the Mariners this year? We’ve spent years preaching the value of outfield defense, especially for a team playing half their games in Safeco Field, and we’ve enthusiastically supported Zduriencik and company as they moved to acquire two elite defensive outfielders this winter. However, as much as we continue to harp on the defense-as-undervalued-asset claim, we’re still aware of the fact that a run is a run, whether it’s produced offensively or saved defensively. We want the team to maximize their run differential, and if there are scenarios that involve Jr in left field giving the team a better chance to outscore their opponent, than that’s the scenario we’re going to support.

So, let’s look into the question – given the current roster, should Ken Griffey Jr ever play left field? And if so, when?

Working off the assumption that Endy Chavez is the current penciled in starting left fielder, we need to evaluate the difference in fielding ability between Chavez and Griffey as well as the difference in offensive ability between Chavez and whoever would be DH’ing when Griffey is in left field. Griffey’s in the line-up either way, so his bat doesn’t really matter for this discussion – we want to know whether there are scenarios where the spread in performance will be larger on the offensive side from having Alternate DH Guy in the line-up in lieu of Chavez than the defensive dropoff from Chavez to Griffey.

First off, let’s start with the defensive difference. Rather than just pointing you to UZR, which is the best defensive metric publicly available, we’ll walk through the defensive opportunities from a big picture standpoint, since I know some of you are skeptical about defensive statistics and because we’re looking for specific situations where it might make sense to put Griffey in LF.

First, the macro view. We can say, with pretty good certainty (thanks to Baseball-Reference), that the Mariners pitching staff will allow something like 1,600 flyballs in 2009. The average major league team gave up 1,621 fly balls in 2008 and 28 of the 30 teams had a total spread of 270 flyballs, ranging from 1,463 (Toronto) to 1,732 (Houston). There was one outlier on both ends, but in general, the spread of team fly balls allowed isn’t all that large. You can bet on something between 1,500 and 1,700 and basically take it to the bank.

Now, of those flyballs, a pretty good chunk are going to fly over the wall, and it wouldn’t matter whether you had Endy Chavez or 74 Ken Griffey Jr’s out there, because those flyballs aren’t going to be caught. If we remove 150 flyballs to account for home runs, that brings us down to 1,450 flyballs in play for the outfielders to try to chase down. How many of those will end up in left field?

Based on spray chart data, the average distribution of flyballs is in the range of 27% LF, 48% CF, and 23% RF. There are more RH hitters than LH hitters in MLB, so LF sees a few more flyballs than RF, while neither corner sees nearly as many as CF.

So, 27% of 1,450 gives us 392 expected flyballs in play to left field. I rounded on the spray distribution percentages anyway, so let’s just call it 400 to make the math easy. If we had a spider monkey on a segway, there are about 400 potential outs to be earned by the team’s left fielder over a full season. Of course, those 400 flyballs aren’t all equally catchable – some will be drives to the gaps that no one can get to while others will be cans of corn that any ambulatory athlete would be able to track down. What percentage of these flyballs can we expect to be turned into outs?

For guidance, let’s look at history. Last year, the Rays did a better job than any team in baseball in turning outfield flyballs into outs, converting 81% of their opportunities by sticking good glove guys in all three OF spots. On the other hand, the Angels only caught about 75% of their opportunities. Of course, these numbers are for the outfields as a whole, not just LF specifically, so the real upper and lower bounds are going to be a bit higher and lower than that – the Angels would have caught a lot less than 75% if they didn’t have Torii Hunter, and the Rays would have caught more than 81% if they had given Eric Hinske’s RF innings to a pure flycatcher. Data from past years confirms these estimates, and we can safely guess that our lower and upper bounds are probably something like 70% and 85% respectively.

In other words, about 70% of all flyballs in play just don’t take much ability to run down. Pretty much any reasonably healthy and skilled major league caliber player would be able to convert them into outs. On the other hand, 15% or so are basically uncatchable for all intents and purposes – these are the almost-home-runs that bang off the wall and the little bloopers into no man’s land that just don’t hang up long enough.

So, we’ve got to use catch rates for Griffey and Chavez of somewhere between 70% and 85%. Chavez is a terrific defensive outfielder, but 85% seems optimistic – let’s put him at 82%, definitely above league average but not into some crazy greatest-LF-glove-of-all-time territory. As for Griffey, well, I think anything above 70% is pretty generous, honestly – he’s been the worst defensive outfielder in baseball over the last three years, and you can’t blame his knee – his worst rate of catching flyballs came in his supposedly healthy 2007 season. But, hey, I like to give the benefit of the doubt to the position that I don’t really hold, so we’ll call Griffey a 72% guy – a bad defensive OF, but not worst in the league.

At those estimates, we’d expect Griffey to catch 288 flyballs (if he played every inning all season long) and Chavez to catch 328 flyballs (ditto on the Ripken season). As you might have already figured out with basic math, if we assume that Chavez will catch 10% more balls than Griffey, and there are 400 opportunities for them both, then that’s a 40 play advantage for Chavez. By the way, this falls directly in line with what all the advanced defensive metrics would predict the gap to be. I just wanted to walk you all through it so you don’t think that someone’s doing gymnastics with numbers to support a preconceived notion.

Okay, so that’s our defensive gap – 40 plays per 162 game season. Each flyball converted to an out is worth about .9 runs (calculated by the distribution of potential outcomes on flyballs and their relative run values), so we’re saying that Chavez would be about 36 runs better than Griffey in the outfield over a full season. 36 runs… this is why we’ve been preaching the value of outfield defense for years. If we were just interested in a macro view, we’d look at that gap, look at the potential bats who would fill in at DH when Junior played the field, and just end the conversation there – there’s nobody in the organization who is 36 runs better with the bat than Chavez over a full season. To make up that gap, you’re looking for a .365ish wOBA hitter, which is something like a Ryan Howard/Carlos Delgado/Derrek Lee. That’s the kind of hitter you’d need to have on the bench to justify sticking Griffey in LF and putting Chavez on the bench from a macro perspective.

However, managers don’t make one line-up on opening day and then see how the next 162 games turn out. They make micro decisions based on the handedness of the other team’s pitchers, the ball in play distribution of their own staff, the park that days game will be played in, and all kinds of other various factors that come into play on a daily basis. What we really want to know is whether there are scenarios where Griffey in LF in lieu of Chavez makes some sense. Of those micro factors that we just mentioned, the two most important are opposing pitcher handedness and batted ball distribution for the M’s starting pitcher.

Essentially, everyone should agree that Griffey should never start in LF against an LHP. Ever. He hasn’t been able to hit lefties for years now, and there’s just no way you could find a RH hitter who would be worth having in the line-up but couldn’t outplay Junior in left field on those days. So, we can pretty much cross 25% of all the games off the list to start off with. If we’re going to find a scenario where Junior makes sense in LF, it’s going to be an when an RHP is starting for the opponent.

However, that’s not a big enough factor on its own. As we mentioned, the bat replacing Chavez wouldn’t be Griffey’s (since it’s assumed he could DH against RHPs), but whoever DH’d in Junior’s place that day. The M’s just don’t have a big thumping LH bat sitting around who won’t be getting playing time if Chavez is in LF. Clement is the closest thing to that kind of player, but there’s every reason to expect him to get significant playing time behind the plate, and any scenario where Clement DH’d and Junior moved to LF, you’d actually be replacing Chavez’s bat in the line-up with Johjima’s, and good luck winning any kind of argument that Johjima is good enough offensively (especially against an RHP) to outweigh the defensive dropoff we’d see in LF.

So, since there isn’t this obvious big bat sitting around that Chavez is keeping out of the line-up, then we need to look for a situation where the defensive difference would be mitigated. The best way to find such a situation would be to look at the ball in play distribution of the team’s starting pitchers.

For now, let’s assume the M’s rotation is set – Felix Hernandez, Erik Bedard, Brandon Morrow, Jarrod Washburn, and Carlos Silva will be taking the hill every five days, with Ryan Rowland-Smith as the #6 guy if someone gets hurt. Could we find a pitcher, or a couple of pitchers, that would decrease the amount of flyballs to left field enough during their starts to shrink the defensive gap to potentially justify using Junior in LF in order to get a better hitter than Chavez in the line-up?

Right off the bat, you can throw Washburn and Rowland-Smith out. As left-handed flyball pitchers, you can guarantee that they’re going to give up more flyballs to LF than the average major league pitcher, and we already know that on average, Junior in LF is a bad idea. There’s no way you want Griffey patrolling left field when you have a LH flyball pitcher on the mound. So, those two are out.

That leaves Felix, Bedard, Morrow, and Silva. To find out how many potential LF opportunities each present per game, I projected their ball in play distributions based on their batted ball histories, then adjusted for handedness, and scaled it to per 30 batters faced in order to line-up with a typical starts worth of potential LF outs.

Felix: 1.20 LF opportunities per 30 batters faced

Bedard: 1.75 LF opportunities per 30 batters faced

Silva: 1.65 LF opportunities per 30 batters faced

Morrow: 1.85 LF opportunities per 30 batters faced

Essentially, 30 batters faced should get you through 7ish Felix/Bedard innings and around 6 Morrow/Silva innings, so the working assumption is that you’d definitely be lifting Griffey for a defensive replacement once you got into the bullpen. Clearly, Felix stands out as the best case scenario here, projecting at least half an LF flyball less per game than everyone else on the staff. In fact, using the projection for Felix of 1.2 LF flyballs per 30 batters faced, you’re looking at .86 catches for Junior and .98 catches for Chavez, or in terms of runs, about .11 runs per Felix start. For the other three, you’re looking at .15 to to .17 runs per start.

So, that’s your defensive gap that has to be overcome to justify starting Griffey in LF given a particular starting pitcher and assuming that the other team has an RHP on the mound that day. Can you make up .11 runs on offense against an RHP with this roster?

Keep in mind, this is .11 runs per 30 batters faced, so Chavez would only get 3 PA in the playing time we’re taking away from him. So, in order to make up that gap, the Alternate DH guy has to be able to be .04 runs per PA better than Chavez against RHP. .04 runs per PA translates to 48 points of wOBA, or about a .280/.360/.470 type of hitter, if you’re looking for an example. How many guys on the Mariners roster who currently don’t have a job do you think can hit .280/.360/.470 against RHP this year? I’m going with zero.

The only possible guy who has that kind of offensive ability and is even potentially going to be on the bench some days is Clement. But, since we set out to try and find a scenario where Griffey in LF makes sense, and we found one that might happen, let’s go ahead and qualify it.

It would make sense to start Ken Griffey Jr in Left Field in 2009 on days where Felix Hernandez is pitching, the opposing team’s starter is right-handed, Jeff Clement is unable to catch but his hitting is unaffected, and you planned on removing Griffey from the game after the sixth or seventh inning.

That’s as good as I can do. Given this roster, Griffey in LF makes sense in that remarkably narrow context, and that remarkably narrow context only. If anyone besides Felix is starting, it’s a no go. If the other team isn’t throwing an RHP, you don’t do it. If Clement is catching, you don’t do it. It’s just a negative proposition in all the other scenarios.

Now, if the M’s can find a LH bat who can post a .360+ wOBA against RHP without giving up much in talent, then we can revisit this conversation. We’re not so set on the Three CF Plan that we’re willing to go forward with a worse team if there’s a better way to win more games.

The problem, though, is that Griffey as an LF doesn’t help you win more games than Griffey as a DH. I know Endy Chavez’s bat isn’t very exciting to most of you, but the defensive difference outweighs the offensive gap between him and practically everyone else on the roster.

This analysis ignores a bunch of ancillary factors – the wear and tear that playing the field could have on Griffey’s health, the potential return on investment from inflating the value of the team’s pitchers with improved defense, the lessened workload on the starting pitchers and the shift in innings towards the starters and away from the bullpen – that also need to be considered in any full scale analysis of who should play the field. However, all of those factors point away from Griffey as an LF, and the deck was already so stacked against the idea that I wanted to try to give it a chance. So, that’s why they weren’t included.

Congratulations, Atlanta!

You placed second in the Ken Griffey Jr. Sweepstakes! Your prize is…

On a one year, $2.5m deal, even though there’s really no where else he could go.

In the words of Precious Roy, y’all are suckers.

I look forward to reading increasingly tortured explanations of how Anderson’s going to help the Braves next year.

Yet another pro-Ichiro post: he’s a Hall of Famer

Every time I hear that the M’s clubhouse is certain to be improved by having a future Hall of Famer there, I yell “they already had one!”

And potentially two, with Felix’s potential.

I’m entirely serious. If you count Ichiro’s NPB time, you’d elect him tomorrow. But if you only count his hitting to date, no credit for defense at all, and you only look at a very superficial stuff that seems to count in voting… Ichiro’s an MVP, Rookie of the Year, 8-time All-Star, 8-time Gold Glove winner, led the league in hits five times, holds the single-season record for hits.

If you use the Black Ink test, looking at the number of times he led the league, he’s right now an above-average Hall of Famer. Same if you use the Hall of Fame Monitor number.

Gray ink, Hall of Fame standards, he’s below average.

You give him any credit for being the first Japanese position player to find such success, which at the time remember was far from a given, and which led the way for Matsui and a host of others, if you give him credit for his defense, and particularly if you’re willing to give him any recognition at all for his time in Japan, he’s a shoe-in.

And that’s not even getting into advanced stat-foo and constructing some serious forward projections at career marks, valuing defense, and so on.

The Mariners have two Hall of Fame hitters in the clubhouse now.

We’ll see if this trend holds up

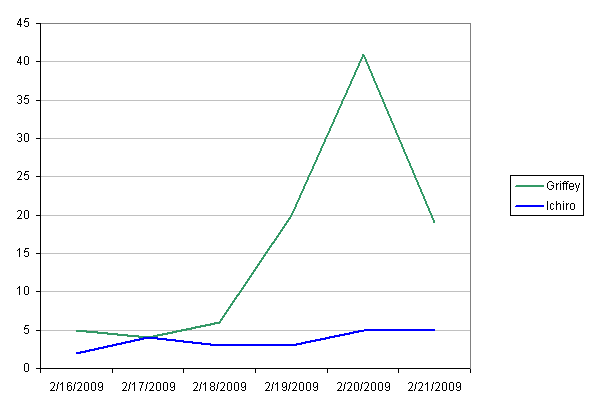

A follow-up to that last post on this. Here’s items on Craigslist with “Griffey” in them charted with “Ichiro” items (some showed up on both).

The image might be clipped, so: Griffey items are in green, Ichiro items are in blue.

Folks, if you’re looking for someone to give your Ichiro stuff to, please let me know.

Selfish Ichiro turns Griffey signing into comment on his own selfish desires

What a jerk. It’s all about what jersey Ichiro bought, and who he idolizes, and his dream that Griffey now shares…

In 1993, 16 years ago, I bought a Ken Griffey Jr. jersey. This is one of my treasures to this day. He has always been a hero to me, and being able to play with him is like a dream come true. Now we share a dream: and that dream is to work hard together and win a World Series.

No wonder Silva hates him so much.

What rapport is that?

This is the lead paragraph in Jim Street’s latest clubhouse chemistry article:

PEORIA, Ariz. — The relationship Ken Griffey Jr. has with Ichiro Suzuki could go a long way in bringing peace and harmony back to the Mariners clubhouse, former Seattle manager John McLaren said Saturday.

It also contains an editorial endorsement of Buhner-as-leader, a quote about Guillen-as-leader, some other random stuff including Chuck Armstrong talking about his days as a lawyer (I thought he was an engineer).

But here’s my question — there’s no mention at any point of a relationship Griffey has with Ichiro. And it’s not “The relationship Griffey and Ichiro will have could help bring the team together…” or “Together, Ichiro and Griffey could bring together the team…” It’s “they have a relationship and it’s going to help…”

We know Ichiro admired Griffey, because he talked about it when he joined the team. But I’m unable to find anything about them being friends now, or talking, or… or anything, really. Ichiro attended a couple of weeks of spring training before the 1999 season as part of an exchange program with Seattle’s sister city Kobe, but finding articles about that’s tough. Still, it’s the only time when Ichiro and Griffey would have been around each other, and we don’t know if they got along. Oddly, it’s not mentioned in the article.

So here — is there anything out there that indicates that Ichiro and Griffey are current friends/friends-of-friends/archenemies? That they have any kind of current relationship at all?

Update the first: Here’s a youtube video of Griffey and Ichiro chilling at dinner. I thought it was 1999 initially, but (as noted in the comments) it’s probably earlier than that, if you try to match his Japanese stats to what he’s saying.

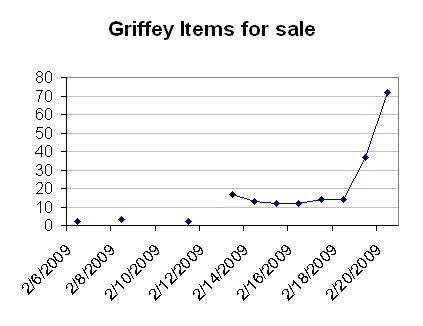

Griffey causes economic boom of sorts

It seems that after Griffey signed, it took a couple of days for everyone to find the Griffey memorabilia they’d stashed in the basement, had kicking around the back of the closet, and get it listed on Craigslist.

That last one’s projected based on the day’s traffic so far.

Pravda proclaims 16k tickets sold yesterday

16,000 tickets! Why, that’s very nearly 200 extra fans a game!

Really, though, the M’s probably just got a 10% return on Griffey’s likely 2009 salary in a day.