The Second Dustin Ackley Lesson

The first Dustin Ackley lesson, I think, is pretty obvious. Don’t ever take any baseball player for granted. Especially a baseball player who hasn’t yet proven himself in the major leagues. Remember, Ackley wasn’t just supposed to hit — he was going to hit, and there wasn’t any question. His defense, sure, there were questions, but his bat? Ackley could wake up and bat .300 while hitting the snooze button. It wasn’t long ago some people wondered whether the Mariners were better off with Ackley or Stephen Strasburg. People talked about Chase Utley upside. It isn’t that I don’t think Ackley is ever going to hit, or that it looks like his entire big-league career is a bust. It’s that we’ve been rudely introduced to the possibility, which previously very few of us considered, or considered enough. Dustin Ackley might not ever hit. Dustin Ackley might not ever be good. Dustin Ackley might end up with a worse career than Jose Lopez. These aren’t untrue statements. The old guarantees that Ackley would produce — those were untrue statements.

Now we have a second Dustin Ackley lesson. Or, if there have been other Dustin Ackley lessons in between, we have another, unnumbered Dustin Ackley lesson. Not long ago, Dustin Ackley made a change to his swing. Not long before that, Dustin Ackley made a change to his swing. This latest change eliminates some of the parts of that older change, with which he showed up to spring training. Ackley hasn’t fully reverted to the way he hit in 2012, but he’s given up on a tweak, as he just never felt comfortable. The results, most certainly, beared that out.

Here’s Ackley on changing his change:

“What I was doing (Saturday), it felt like the same thing without having to do a bunch of the timing before it,” Ackley said. “It’s still trying to accomplish the same things. It’s really not that big of a difference. It might be 6 inches from where I started before. It’s not like I’m changing my swing. It’s still the same swing, but I just don’t have the timing of getting it started.”

Okay, hey, great. Now here’s Ackley from February, when he came to camp and faced the pitcher in the box, rather than having his shoulders parallel with the plate:

“It just puts me in good hitting position,” he said. “Last year, with the old stance I had, there was no separation, my hands, and everything. I worked on it a lot this offseason just to get that feel of maybe what it used to feel like, as opposed to last year when I didn’t really know what was going on. I think that was important for me this offseason.”

This lesson is less about Dustin Ackley specifically, and more about baseball players in general. Baseball players are constantly changing things around, especially when their performances start to slip. Particularly in spring training, you’ll hear about adjustments that have been made, or that are in the process of being made. If a player under-performed in Year X, the next year he’ll probably talk about tweaks that he hopes will allow him to leave the struggles in the past. The talk will be accompanied by explanations, and it’s the same for both hitters and pitchers.

There are two things that are important to keep in mind, for all players:

- not all attempted changes will be successfully, sustainably implemented

- not all implemented changes will work

The first one has a lot to do with muscle memory. By the time a player gets to the highest levels of professional baseball, he’s put in a lot of reps, many of them doing the exact same things with the exact same motions. Adjusting a swing isn’t as easy as identifying a thing to change and then changing it the next day. Pitching mechanics are even more complicated, and you never know what sort of cascading effect a mechanical tweak might have. If a player doesn’t feel comfortable, he doesn’t feel comfortable. There’s also the case where players are initially receptive, then they revert to familiar motions in higher-stress situations where they’re going on autopilot. A particular case where a lot of us slip up is with pitchers learning new pitches. If a guy is trying a cutter in March, that doesn’t mean a cutter is going to be a part of his repertoire going forward. Learning pitches is hard. Even the cutter, which I think is pretty simple and straightforward.

And then there’s the second one, which we’re reminded of from the Ackley example. Dustin Ackley thought his tweak would work, and that’s why he practiced it and took it into the spring. It didn’t work, because he couldn’t find his timing, and the stance tweak has been abandoned by the middle of April. Every single time a player makes a change, and explains it, he’ll explain it positively, he’ll explain it as a solution. If a player didn’t feel like a given change was a solution, he wouldn’t try to make the change in the first place. Everybody is always initially optimistic about tweaks, but then what we find is that struggling players usually continue to struggle, because they aren’t good. Baseball is a complicated, difficult game, and the difference between a good version of a player and a bad version of a player generally isn’t one little part of his mechanics. And even if you feel like an adjustment is the right thing, you can’t know how it’s going to help until you actually take it into competition. You can only guess, and sometimes people guess wrong. They don’t mean to. Baseball’s just hard.

I think this is one of the reasons people tend to be optimistic about their teams come spring training time. The good players are good players, and the bad players mostly made changes to try to make themselves better players. And you believe in those changes, because everybody who talks about them is positive about them. It’s easy to see how a handful of tweaks could make a handful of under-performers better, and presto, just like that, 81 wins. 90 wins. 100 wins! Amazing baseball team!

Players are almost always changing in some way or another. Most of the time, these changes are very, very small, essentially imperceptible. Sometimes the changes are more dramatic, and sometimes the changes are successfully implemented. Sometimes said changes are effective. Other times they’re not. We have to keep in mind the cases where they’re not. It just isn’t easy to get better.

Game 15, Tigers at Mariners

Aaron Harang vs. Doug Fister, 7:10pm

The newest Mariner faces off today against an ex-Mariner, giving everyone a chance to sigh and wonder what the hell happened with that trade. Casper Wells was DFA’d by the Blue Jays, and Charlie Furbush is a perfectly serviceable lefty bullpen arm, but it’s always tough watching six feet eight inches of walking, talking, hitting-the-blacking evidence of the fallibility of talent evaluation, and how bad we are (bloggers, fans, GMs, analysts, talking heads) at predicting the future. Doug Fister is now throwing a bit slower with the Tigers than he did in any previous April, but it doesn’t really matter – his game was never about velocity. His ground ball rate has continued to climb, and is now solidly over 50%. A big part of this is that he’s all but shelved his four-seam fastball (which he threw almost exclusively when he first came up in 2009) for a two-seam sinker. This started before the trade, but better feel for the pitch has probably helped him. He’s made a lot more use of his curve ball since becoming a Tiger, particularly against right-handed batters, and that may account for his higher strikeout rate.

Aaron Harang is basically a fastball/slider guy, who generates a lot of fly balls. Early in his career, he got enough strikeouts to mitigate the HR problems that came with his pitching style; he put up back to back 5 WAR seasons for the Reds several years ago. But starting in 2008, the small park + fly ball combo was too much, even for his above-average K:BB ratio to overcome. Interestingly, the bulk of his HR problem has come against same-handed hitters. Almost everything in his splits are even – K rate (actually better vs. lefties), average, BABIP, etc. His walk rate’s worse versus lefties, but the big thing that sticks out is his HR rate, which is clearly higher against righties. Why? Well, I have no idea, but he throws four-seamers almost exclusively to righties, and he throws his two-seamer/sinker to lefties. And his HR problems have been worst with his four-seamer. The result is that his HR rate gives him reverse splits by FIP, and perfectly normal splits by xFIP. I’m sure someone’s talked to him about it, but I’d mix in a few more two-seamers to righties. We already know that two-seamers have much larger platoon splits than other kinds of fastball, which makes his usage patters counter-intuitive, to say the least. He’s now in what we’d assume is a good park given his skill set (though not as good as last year), but keep in mind he’s not going to run the kind of K rates he ran in recent years anymore – his K rate against non-pitchers is in the 15.5% range, as opposed to the 16.5-17% marks he posted. That’s not a huge deal, but it could have spillover effects on things like his strand rate. All of that said, it’s tough to complain about his acquisition.

I know many of you are sick to death of sports business/revenue type posts, so I’d advise you not to click on my post about the risk in the ROOT sports deal or Dave’s on the moneymoneymoney the M’s stand to gain.

With Stephen Pryor on the DL with a torn lat muscle, the M’s have brought up Yoervis Medina from AAA Tacoma. He’s gone from a bad starter to something of a joke amongst 40-man roster observers to a quietly effective reliever. Medina throws a hard, heavy fastball in the mid-90s (and you wondered why he was still on the 40-man) and gets a decent number of grounders. I still think Carson Smith is the best pitcher with this basic template in the system, but Medina’s much more ready. I’ll be fascinated to see how he does; he’s been excellent in his very, very brief tenure with Tacoma.

Good to see both Guti and Mike Morse back in the line-up. Here’s hoping they’re able to go at 100%, and that Morse’s pinky injury doesn’t impact his swing.

Line-up!

1: Gutierrez, CF

2: Seager, 3B

3: Morales, DH

4: Morse, RF

5: Ibanez, LF

6: Smoak, 1B

7: Shoppach, C

8: Ackley, 2B

9: Ryan, SS

SP: Harangutan

As Dave mentioned on twitter, that’s Shoppach’s 4th start in 6 games. We’ll see if this pattern continues and if/where the M’s deploy Montero.

Ryan Divish has a good post on Ackley using his off-day to rework his pre-swing routine. Gone is that very open stance as the pitcher goes through his delivery, and he’s back to something similar to last year’s swing.

Ok, something slightly more up-beat: Larry Stone has a great interview with Mike Zunino. I saw Zunino a bit this weekend, so I’ll try to organize some thoughts on him too.

The ROOT Sports Acquisition and Risk

I wanted to follow on Dave’s great post about the RSN acquisition. I’m broadly in agreement with Dave and essentially everyone else that this is almost certainly going to give the M’s a lot more revenue, particularly in the medium term. The overall revenue stream will get bigger, and the M’s will keep more of it. But I haven’t seen a whole lot of discussion about the risk involved, and while I think the upside is more tangible and likely, that doesn’t mean we can ignore the risk completely. As I mentioned in 2012, what we’ve seen in TV deals the past few years bear the hallmarks of a bubble. RSNs are paying skyrocketing rates for the rights to televise baseball games even as fewer people are watching baseball. They’ve had free rein to push for higher and higher carriage fees with cable carriers (Comcast, DirecTV, DISH Network, Time-Warner, etc.) and consumers have, in general, paid up. Part of the calculus here is that live sports are an effective antidote to DVR technology, meaning advertisers will reach more eyeballs than they would with a highly rated drama series, where many people DVR the show and skip the ads when they play it back. In addition, many of the RSNs get better ratings than national titans like ESPN, which makes sense if there’s a game on the RSN and yet another SportsCenter on ESPN.

But what happens when carriers start to balk about the spiraling carriage fees? This isn’t a theoretical problem. Last year, the Houston Astros and Rockets created their own RSN, Comcast SportsNet Houston, in a billion dollar deal. This would supposedly transform the Astros revenue, as they had the worst TV ratings in baseball in recent years (for obvious reasons) and a poor deal with Fox Sports Houston. The problem is, cable operators in Houston have been holding out, and thus DirectTV, DISH Network, and Time-Warner cable don’t carry the network. Again, the brand new network that has the rights to the Astros, the Houston Rockets (who are in the NBA Playoffs this year!), Rice and University of Houston football, *is not available on most carriers in Houston*. The same thing’s going on to a lesser extent in San Diego, where Time-Warner’s balked at the new Fox Sports San Diego’s carriage fee demands after the latter acquired the rights to the Padres games (and gave the Pads a 20% equity stake as well). Local government officials are involved in both Houston and San Diego, trying to help broker a deal.

So Comcast and DirecTV have battled tooth and nail in Houston, with rival campaigns and websites. Now, DirecTV has a stake in ROOT sports, and while Comcast already carries the network, I can imagine that negotiations when the current agreement is over will be, um, intense. Operators are trying to stave off customers cutting the cord and moving to netflix/roku type devices, and at the same time offer advertisers the kind of un-DVR-able programming that live sports provides. It’s making all negotiations a lot more contentious, as many of you saw in Tacoma when city-owned operator Click Network stopped carrying local ABC affiliate KOMO when negotiations hit a wall. That’s led to lawsuits and a fascinating* lawsuit involving whether these rates are protected trade secrets. Similar disputes are happening elsewhere, as the industry’s still adjusting to new technology, deregulation in the 1990s and increased costs.

In an ideal world, the new ROOT Sports comes to some sort of agreement with a new NBA team and a potential NHL team that would give them a lot more leverage than the M’s could on their own (“Seriously! We have prospects! Good ones! Stay tuned!”). Unfortunately, the M’s may not be on Chris Hansen’s christmas card list after their objections to his SODO arena proposal. They’re talking, though not about the network, and after an awkward start, the M’s have said all of the right things about their potential new neighbors recently. And in any event, Comcast may want to partner with a new team to give them leverage in any possible fight with DirecTV. Of course, the Houston experience shows that even if one company acquired the rights to all of the local teams, that wouldn’t necessarily be a guarantee that they could extract the fees they expect from cable providers. A balkanized TV sports world hurts everyone, especially consumers; I’d guess that the overlap between basketball fans and baseball fans is pretty substantial. I also know that ROOT will work hard to come to a deal with Comcast, and they may get one lasting several years. All of these risks are down the road and speculative. But the parallels to the housing market circa 2006 are starting to get eerie. The M’s made a completely logical decision to do what other teams have done and purchase their own cash cow. One that will pay them 2X or 3X more than what they got in 2007! Everyone’s doing it, you know. With values tripling within a few years, why, you can’t afford NOT to. People will *always* tolerate sizable annual rate increases.

* if you’re really geeky and also bored

Mariners Take Majority Ownership of ROOT SPORTS NW

We’ve known for a while that the Mariners had an opt-out in their agreement with ROOT SPORTS, and were going to be able to renegotiate their contract based on the fact that television revenues for Major League teams are skyrocketing right now. Because live sports are mostly DVR proof and not (legally) available through streaming sites, cable companies are investing very heavily in exclusive long term contracts for sports franchises, especially baseball, because it offers 162 broadcasts per year.

Instead of re-signing to a new deal with ROOT — currently owned by DirecTV, by the way — the Mariners have bought a majority stake in the network. What this means is that instead of simply licensing their television rights, the Mariners will generate revenue directly from the network, much like the Yankees do with YES. Wendy Thurm laid out all the different television contract arrangements in a great post at FanGraphs last year, so you can see there that the Mariners will join the Yankees (YES), the Mets (SNY), the Red Sox (NESN), and the Orioles/Nationals (MASN) as owners of their own RSN, rather than striking a licensing deal with an existing cable network.

The big advantage of owning your own network is having a separate entity in which to hide revenues and keep them from going into the revenue sharing pool that MLB takes a 34% cut from to distribute among the lower revenue clubs. If the Mariners had signed a deal that simply caused DirecTV to cut them checks for their broadcast rights, the team would have had to disperse 1/3 of that to MLB. As owners of the network, the Mariners will simply be able to claim that revenue as ROOT SPORTS revenue and not Mariners revenue, and thus won’t be subject to the same revenue sharing rules. It’s a loophole, but it’s one that MLB has not yet seen fit to close. It doesn’t mean they won’t close it eventually, but it’s more difficult to track revenues of affiliated companies than it is to track what the teams have to disclose as income, so it’s likely that this partnership will result in the team being able to keep a larger percentage of their television rights money than if they had struck a pure licensing deal.

What this will mean is that the Mariners are going to have a significant increase in revenues going forward. Under their current television deal, the publicly available information has the team bringing in about $45 million per year, or at least that was the average during the life of the deal – it might be higher at the moment if the deal was backloaded. Every team who has signed a new licensing agreement with an RSN over the last few years has done significantly better than that AAV, ranging from $60 million per year (plus a 20% equity stake) for the Padres to $280 million per year for the Dodgers. That the Mariners chose to take a controlling stake instead of signing a licensing deal means that they believe they can make even more money by controlling the RSN than they would have by signing those rights away, so while we’ll never know exactly how much the team will get from owning a good chunk of ROOT, you can bet it’s going to be a sizable raise.

So, yes, the Mariners payroll is going to go up, and probably go up a good amount next year. Pretty much every new TV deal has been met with a payroll increase for the team that signed the contract, even among the lower revenue teams. The Indians just signed Nick Swisher and Michael Bourn over the off-season in large part because of the deal they struck to sell SportsTime Ohio to Fox Sports. Don’t be surprised if the Mariners are among the most aggressive teams in free agency next winter. This is generally how things work after a team signs a new TV deal or creates their own RSN.

But, at the same time, you have to realize that this isn’t a Mariners specific thing. The Mariners are taking part of a trend that is pushing up the revenues and the payrolls of every Major League team. Relative to the rest of the league, the Mariners had to do this just to keep pace. Having their own RSN doesn’t instantly make the Mariners into the Yankees. They’re just jumping onto the wave that is lifting all Major League clubs at the moment, and so they’re going to have more money to spend, but when everyone has more money to spend, players just get more expensive.

And, as we’ve talked about, free agency is changing. The wave of long term extensions for players like Felix Hernandez and other teams’ versions of Felix mean that premium young talents aren’t getting to FA early in their careers any more. Money that used to go into luring away star players is now being used to keep star talents with their original organizations, and so the players who actually change teams are of lesser quality — or are just older — than they used to be. The Mariners may very well go into this coming off-season with a lot of money to spend, only to find that the best players available are Jacoby Ellsbury and Matt Garza. Franchise saviors aren’t hitting the market much anymore.

It doesn’t make that money useless, though. In my opinion, the new advantage of financial resources is going to come through a heightened ability to make trades. While MLB teams haven’t traditionally sold off their best players, I wouldn’t be surprised if teams like the Rays and Marlins begin to look for some kind of financial compensation when they put David Price and Giancarlo Stanton on the trade block. The commissioner’s office might not go for large cash transfers, but there are creative ways that low revenue teams can get teams flush with cash to provide them some financial flexibility. Maybe instead of just asking for five good prospects, the Rays would want the Mariners to sign Taijuan Walker to a guaranteed six year contract with a bunch of team options for $40 or $50 million guaranteed and then agree to pay Walker to pitch for the Rays for the next decade. Would MLB go for this? I don’t know, but this is the kind of thing that a team with money to burn and no obvious free agent targets could try.

And now the Mariners are going to be that kind of team. The payroll is going to go up, and they’re going to be more aggressive in player acquisition than they have been. This isn’t an unexpected gift from the heavens, as they’ve known this windfall was coming and it was part of the motivation behind the Felix Hernandez extension, but it’s still going to be a financial boost to the team. It doesn’t make them the richest team in baseball or anything, but you can bet that the team almost certainly isn’t going to run an $85 million payroll again next year.

One final note – if your plan is to respond to this post with a rant against ownership being cheap bastards who are just pocketing all the money and screwing the fans because they don’t want to win, don’t bother. In fact, go away. You don’t know what you’re talking about. The perpetuated myth that the team is intent on screwing you out of your money by putting a bad product on the field is stupid and wrong. Winning teams make more money than losing teams. If the Mariners were completely and utterly intent on maximizing profits with no regard for anything else, they’d have invested more heavily in the product, because winning breeds revenues. It isn’t a lack of desire to win, or a preference for profit over winning, that has caused the team to stumble the last decade. They just made a bunch of bad baseball decisions that ended up doing real long term harm to the franchise. It is as simple as that. They aren’t losing on purpose. Stop believing that crap.

Mariners Holding Their Own Against Top Teams

| MARINERS (6-8) | ΔMs | TIGERS (7-5) | EDGE | |

| HITTING (wOBA*) | -3.7 (20th) | 2.3 | 16.5 (3rd) | Tigers |

| FIELDING (RBBIP) | 2.5 (12th) | 0.4 | 1.5 (16th) | Mariners |

| ROTATION (xRA) | 1.3 (13th) | 2.0 | 5.7 (6th) | Tigers |

| BULLPEN (xRA) | -0.6 (18th) | 0.9 | -0.6 (17th) | — |

| OVERALL (RAA) | -0.5 (16th) | 5.6 | 23.1 (3rd) | TIGERS |

The Mariners split their four-game sets with Oakland and Texas but have dropped to Chicago and Houston. Because, baseball.

Still, the news of the day will not be the forthcoming bullpen move to replace Stephen Pryor, but that the Mariners have finally done what many of us long suspected and started building a partnership group for a regional sports network.

Few actual details are available, but I’m doubting that it makes the Mariners worse off in terms of revenue. As with other recent deals, this one is a doozy in length, lasting until 2030, so both parties had to feel comfortable with growth projections to lock in together for that length.

It’s Easy, Not Easy To Be Carter Capps

Carter Capps is a player in major league baseball! He’s 22 years old and two years ago he hadn’t even been drafted yet, from a little school you couldn’t place on a map. He’s young, he’s loved, he’s healthy, he makes good money doing what he’s good at, he’s already earned his boss’s trust, and he’s blessed with the sort of raw stuff most relievers would…well I don’t know if anybody would kill for Carter Capps’ stuff, but plenty of people would probably willingly break the law. Carter Capps has an awful lot going for him, and better days probably still lie ahead. Capps has things as figured out as any young reliever can.

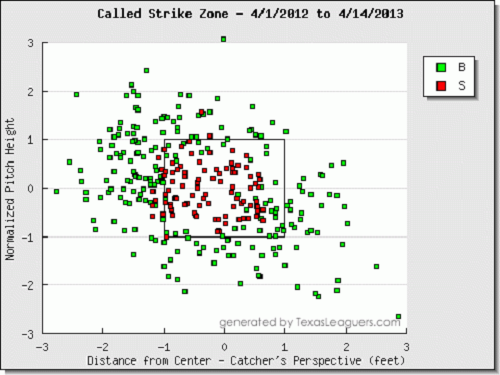

But boy has Capps ever gotten boned on the strike zone. Ryan Divish tweeted a few things on Sunday to the effect of Capps not getting the benefit of the doubt because he’s inexperienced, he throws from a funky arm angle, he doesn’t have great command, and his pitches really move. There’s also the matter of the people who have been catching Capps in games. But anyhow, check out Capps’ called strike zone since his debut, courtesy of Texas Leaguers:

Thanks to StatCorner, we can also put that into numbers. A league-average reliever has had about 15% of pitches in the strike zone called balls, and about 6-7% of pitches out of the strike zone called strikes. That strike zone is defined as the strike zone that’s actually called, not the strike zone in the rule book. Capps, meanwhile, has had 29% of his pitches in the strike zone called balls, and 4% of his pitches out of the strike zone called strikes. Now, that’s only counting pitches not swung at, and with Capps we’re dealing with samples of about 120 pitches taken in the zone and 189 pitches taken out of it. These samples are little and so these samples and the other results come with considerable error bars. But in the early going, the numbers back up the claims — Capps is not an easy guy to catch, and he’s not an easy guy to call. So he ends up with pitches that aren’t balls getting called balls, as a consequence of how unusually talented he is.

Some of this should go away as Capps establishes himself as a big leaguer. Some of this should go away as Capps stops pitching to Jesus Montero. Some of this should go away if Capps improves his command. And this isn’t preventing Capps from succeeding — he’s still thrown nearly two-thirds of his pitches for strikes, and he’s got 38 strikeouts in 32 innings. The neat thing about Carter Capps is that his stuff is so good he doesn’t need a generous strike zone, or even an average strike zone. He’ll work with what he’s given and he’ll still make hitters miss, and I’m guessing he won’t keep running a .382 BABIP. Capps is already good, as things are.

But Capps hasn’t been treated fairly. I’m not even necessarily blaming anyone. I can’t imagine what it’s like to catch a guy who throws like that. It’s probably hard enough to catch Joe Saunders. I can’t imagine what it’s like to call a guy who throws like that, since I imagine I’d constantly be flinching and covering my junk. I get why things are the way they are, but I’d love to know how Capps could look if he pitched to the same zone as most of the rest of the guys in the league. Just because this smaller zone is sort of a tax on a guy with better-than-average stuff doesn’t make that fair to the guy with better-than-average stuff. All pitchers should pitch with the same rules.

Carter Capps is going to make hitters swing and miss. At least for the foreseeable future, he’s going to have to, because called pitches haven’t treated him very generously. Congratulations on not thinking about how Dustin Ackley sucks for the last five minutes. Oh, crap.

Nothing You Couldn’t Have Guessed

For the record, before we begin, know that it’s uncomfortable and weird to be writing content about baseball on a day like today. I can see how it could be interpreted as insensitive and tactless, and you’re free to feel however you feel, but if part of the purpose of sports is to provide a reliable constant, to be a rock in the whitewater, then we should be looking to them now more than ever. After donating blood. Donate blood. Now on to sports. Stop reading if you don’t think it’s right to be reading.

On Saturday, against the Rangers, the Mariners lost, but they lost close and they lost late. They lost because two runs scored against Carter Capps, but before those runners crossed the plate, Capps had a ball called on what he thought was a strikeout. Given that strike, things would’ve gone differently. On Sunday, against the Rangers, the Mariners won, but they barely won, and earlier a controversial ball call with Brandon Maurer on the mound helped the Rangers to take the lead. There are missed balls and strikes in every single game that gets played, but this past weekend, there were missed strikes of import. Mariners pitchers weren’t given particularly generous strike zones.

You probably feel like umpires haven’t been kind to the Mariners this season. Truth be told, probably every fan base feels that way about umpires and their team, but in the Mariners’ case, it turns out the feeling is justifiable. The season’s only just underway, but it didn’t take long for the Mariners to find their way to the bottom of a leaderboard. Or the top of a leaderboard! If you sort in the opposite order. Gotta think positively.

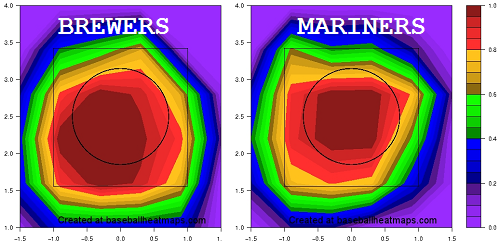

It’s possible, using plate-discipline data available at FanGraphs, to derive a sort of “expected strikes total”. One can then compare this against a team’s actual strikes total, to see how the zones have been. It’s not a flawless statistic, but it’s an interesting statistic that doesn’t mean nothing. So far this season, across the entire league, the average difference between strikes and expected strikes has been -2 per 1,000 called pitches. In the lead we find the Brewers, at +67 per 1,000 called pitches. At the bottom we find the Mariners, at -45 per 1,000 called pitches. That is, on a per-1,000 basis, the Mariners have been 43 strikes worse than the average, and 112 strikes worse than the Brewers.

The Mariners, as a team, are creeping up on 1,100 called pitches, in order to give you some reference for that denominator. I admit it isn’t the best denominator or the most intuitive denominator but I really like the roundy feel of a thousand. How much do numbers really mean at this point in the year? I went back to 2012 and compared April numbers against full-season numbers. The r-value came out to 0.78, and that doesn’t control for changes in personnel. Turns out these numbers matter, and they’re reflecting a skill or shortcoming. The Mariners, again, look like they’ll be given a smaller strike zone than most other teams.

Via Baseball Heat Maps, let’s compare the Brewers’ 2013 strike zone against the Mariners’ 2013 strike zone:

Now, that’s a comparison between the league’s best and the league’s worst, not the league’s average and the league’s worst. And of course, most of the Mariners’ strikes are called strikes, and most of the Brewers’ balls are called balls. But it’s about incremental differences in percentages, and the Mariners get more balls on pitches in the zone, while the Brewers get more strikes on pitches out of the zone. Something is working for the Brewers. That same thing is not working for the Mariners.

And a lot of this, predictably, presumably has to do with the catchers and with pitch-receiving. Jonathan Lucroy is an absolutely fantastic receiver, every bit as good as Jose Molina even though Molina gets a lot of the sabermetric attention. With Seattle, Jesus Montero has gotten a lot of the time behind the plate, and Montero is kind of an all-around catastrophe. The thing about receiving is that it’s very subtle, and an untrained eye won’t spot the difference between the best and the worst at it. But Montero is one of the worst at it, and here’s where that’s showing up.

Montero hasn’t caught all of the innings, and Kelly Shoppach might deserve some of the blame. Additionally, maybe the Mariners haven’t had a representative sample of umpires, and maybe the Mariners’ pitchers haven’t been doing their catchers any favors with inadequate command. The wrong thing to do would be to look at this and conclude “well Jesus Montero sucks”. It’s by also looking at the rest of Jesus Montero’s game that that conclusion can be reached.

Jesus Montero is not a good defensive catcher. John Jaso is not a good defensive catcher. Miguel Olivo is not a good defensive catcher. Josh Bard is not a good defensive catcher. Adam Moore is not a good defensive catcher. Rob Johnson is not a good defensive catcher. Kenji Johjima was not a good defensive catcher. And so on. It’s been a long time since Dan Wilson, who’s probably under-appreciated by the statistical community, and Montero is only continuing an organizational pattern. Unsurprisingly, Montero probably isn’t going to be a catcher for very long. Unsurprisingly, the Mariners are in love with Mike Zunino, because Mike Zunino might actually be a passable catcher in all facets of the game.

So if and when Zunino comes up, we could see these numbers start to change. I don’t know how Zunino is as a receiver, but it’s hard to imagine he’s worse than Montero is. The Mariners might manage to pull themselves out of last, and of course this isn’t the reason why the Mariners probably aren’t going to make the playoffs. That has more to do with the rest of the pitches thrown, and with the hitting and the defense. This is just a little factor. It’s felt like the Mariners haven’t pitched to a normal-sized strike zone. This is because the Mariners haven’t pitched to a normal-sized strike zone. And how! League’s worst. Nowhere to go but up, or down, deeper in the hole.

Why Mike Zunino Needs More Seasoning

I like Mike Zunino a lot. I think he’s going to be a very good player, and he might be the best catcher in the Mariners organization right now. I think he’s been generally underrated as a prospect because his tools aren’t so flashy, but his combination of skills project out to star level quality. I’m probably more excited about Zunino than I have been about any Mariners prospect in a while.

And, yes, his early results down in Tacoma have been excellent. With Jesus Montero looking more and more like a bust — at this point, I don’t see him as a productive Major League player any time soon — the M’s are going to be tempted to call Zunino up sooner than later. I think they’re probably best holding off for a while, and it has nothing to do with service time or Super-Two status. It has to do with his contact rate.

You’ve seen all of Zunino’s good numbers. You know his overall line is great. Here, however, are the contact rates for all of Tacoma’s hitters this season*:

| Name | Age | PA | Pitches | P/PA | Strike% | Swing% | Contact% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jesus Sucre | 25.17 | 11 | 49 | 4.45 | 59.2% | 40.8% | 90.0% |

| Carlos Triunfel | 23.33 | 47 | 182 | 3.87 | 68.1% | 48.4% | 85.2% |

| Nick Franklin | 22.25 | 21 | 82 | 3.9 | 69.5% | 53.7% | 84.1% |

| Nate Tenbrink | 26.5 | 45 | 165 | 3.67 | 59.4% | 43.0% | 83.1% |

| Scott Savastano | 27 | 17 | 80 | 4.71 | 57.5% | 32.5% | 80.8% |

| Endy Chavez | 35.33 | 31 | 113 | 3.65 | 61.1% | 36.3% | 80.5% |

| Rich Poythress | 25.83 | 43 | 167 | 3.88 | 61.1% | 35.3% | 79.7% |

| Alex Liddi | 24.83 | 50 | 182 | 3.64 | 59.3% | 42.9% | 74.4% |

| Eric Thames | 26.58 | 49 | 202 | 4.12 | 62.9% | 47.5% | 72.9% |

| Mike Zunino | 22.25 | 37 | 126 | 3.41 | 65.1% | 47.6% | 71.7% |

| Carlos Peguero | 26.33 | 50 | 164 | 3.28 | 72.6% | 56.1% | 71.7% |

| Denny Almonte | 24.75 | 27 | 111 | 4.11 | 67.6% | 51.4% | 49.1% |

*Minor league pitch data isn’t as good as major league pitch data, so none of this is gospel. These numbers could be somewhat incorrect, but the general idea is probably right.

Mike Zunino has the same contact rate as Carlos Peguero. He’s making less contact than Eric Thames or Alex Liddi. We’ve seen these guys at the big league level, and we’ve seen how major league pitchers exploit an overly aggressive approach. Despite their power, they’ve flopped in the majors, because they simply don’t control the strike zone well enough to be real offensive contributors.

Zunino is better than these guys, and the bar for offensive production is lower because he’s a catcher, but if Triple-A pitchers are getting him to miss on 30% of his swings, you shouldn’t expect him to do much better against Major League pitchers, and the list of Major League hitters who have succeeded with contact rates in the below 70% is very small.

Long term, I don’t think this is going to be a huge problem. Zunino posted a very high contact rate in his short stint in Jackson last year, and he’s shown a good approach at the plate both in college and in his prior minor league stints. We’re dealing with a sample of 126 pitches. The first 126 pitches a guy has seen from Triple-A pitchers. Pitch selection is something that improves with experience, and Zunino has very little.

But that’s why the minor leagues exist. They’re not just for fringe big leaguers to hang around and wait for someone to get hurt. Zunino is getting valuable experience against guys who can spin breaking balls and get him to chase pitches out of the zone. He’s good enough to punish their mistakes, but he also needs to learn how to lay off pitches that he can’t destroy. It is better for Zunino to learn those things in the minor leagues. Not only should the organization should be hesitant to start his service time clock, the Mariners should be hesitant to expose yet another young player to a frustrated fan base that is used to seeing every offensive prospect turn into a bust. If the Mariners bring Zunino up and he hits like Aaron Hicks has in Minnesota or Jackie Bradley Jr has in Boston, it could be damaging to both his development and the psyche of an already frustrated fan base.

Because of how fast he rose through the minors, Buster Posey is the often used optimistic comparison for Zunino. During his 359 plate appearances in Triple-A, Posey posted a 14.7% strikeout rate. Not only did the Giants give him a half season at the minors highest level, they also didn’t give him a regular job until he showed he wasn’t fooled by minor league pitchers. Given how well he performed after getting the call, you could argue that he might have been ready earlier, and I’m not sure Zunino will need 359 Triple-A plate appearances before he’s ready for the majors, but I would like to see him controlling the strike zone better than he is right now.

And that’s not something that you can rush. The power is tempting, but undisciplined power hitters get to the big leagues and get exposed all the time. The Mariners should avoid getting seduced by the power and evaluate how well the total package will work in the Majors. Until he starts making better contact, it’s best to let him get that experience in the minors. He’ll be ready soon, but rushing him won’t help Zunino or the Mariners.

Game 14, Rangers at Mariners

Brandon Maurer vs. Nick Tepesch, 1:10pm

The M’s head into their first off-day of the season needing a win to get a split and avoid dropping three straight series losses. Brandon Maurer’s shouldering a bit more pressure than his teammates, as he’s got to know he can’t have a repeat of his 2/3 of an inning performance against Houston. As many have mentioned, Danny Hultzen’s in the same spot in the rotation just 30 miles away; Hultzen will start today against Salt Lake in Tacoma in what amounts to another job interview. He wouldn’t accrue a full year of service time if he was brought up soon, and while the M’s don’t want to yank Maurer out of the rotation so quickly, *2/3 of an inning, at home, against the Astros.*

What’s his problem been? I have to say I’m a bit surprised it’s gone as poorly as it has, but there are some issues he could conceivably work on. First, his release point is all over the place. It doesn’t look too bad averaged, but his fastball release point can vary by over 6″ within a single at-bat. During the spring, I was worried that he had a decidedly lower/more towards third base release for his slider and change. It was subtle, but MLB hitters are selected in part on their ability to detect and interpret information like that. From what I can tell, that hasn’t been a big problem in his first two starts. Instead, he’s all over the place with all of his pitches. Maybe there’s a theoretical benefit to that, but given he’s had clear problems putting his pitches where he wants them, any gains in batter confusion remain hypothetical for Maurer.

The other issue is pitch sequencing. In his second game, Maurer fell into a pattern of throwing his slider (or the change, in Pena’s case) for his 3rd pitch of an AB. It may have been nothing, or just coincidence, given that he didn’t get through an inning, but he and his catcher should mix things up a bit more. Part of that may be throwing more fastballs. In his first game, he threw fastballs in a minority of his pitches. You can’t really take anything from his second start, but he’s clearly attempting a mix that’s not all that common. Madison Bumgarner of SF is probably the most successful pitcher to rely on his slider so much, but given how rudely MLB hitters have treated Maurer’s, maybe it’s time to use that pitch in a different way. More than anything, he’s just got to avoid hanging it. Even with two strikes, he’s had lapses where he leaves a slider up and out over the plate. That can’t continue today.

The Rangers start their *other* out-of-nowhere back of the rotation rookie, Nick Tepesch. Justin Grimm fared reasonably well in the Rangers win over King Felix, so the Rangers will hand the ball to another unheralded right-hander in Tepesch. Tepesch was a 14th round pick in 2010 after an up-and-down college career at Missouri (sounds a lot like Grimm so far), and though his draft position doesn’t reflect his talent (he signed over-slot), he was clearly a little lost in college, giving up 250 hits and 147 runs in 213 innings. As a pro, he’s used solid command of a fastball, curve and slider/cutter to limit walks and runs. The fastball isn’t great, averaging around 91 MPH, but he gets good sink on his two-seam/sinker, resulting in good ground ball rates.

He tends to use the sinker more to lefties and saves his straight-as-an-arrow four-seamer for righties, which is a bit odd, but hey, he’s the 14th rounder who’s already in the majors. He’s had issues with long balls here and there, and righties have actually hit more of them on a rate basis. He balances that with a better K:B ratio, so on balance, his splits are pretty standard.

The M’s line-up:

1: Chavez, CF

2: Bay, RF

3: Morales, DH

4: Ibanez, LF

5: Smoak, 1B

6: Seager, 3B

7: Montero, C

8: Ackley, 2B

9: Andino, SS

SP: Maurer. C’mon kid.

Hmm, still no Gutierrez.

I’ll be at the Rainiers game watching Hultzen; game time is 1:30. Jimmy Gilheeney starts for Jackson, and Matt Anderson will start for Clinton. Trevor Miller goes for High Desert.

Game 13, Rangers at Mariners

Joe Saunders vs. Alexi Ogando, 7:10pm

I’ve been at CenturyLink Field today, watching a team off to an even more disappointing start than the M’s. I did hear that Franklin Gutierrez’s leg tightness has returned, necessitating a second consecutive Ibanez/Chavez/Bay outfield. Don’t mock it; they’re undefeated in the ‘victory’ formation.

Line-up

1: Chavez, CF

2: Bay, RF

3: Morales, DH

4: Ibanez, LF

5: Smoak, 1B

6: Seager, 3B

7: Shoppach, C

8: Ackley, 2B

9: Ryan, SS

SP: Saunders

The Rainiers are continuing yesterday’s home opener today. Mike Zunino has another RBI already, and Ferris HS grad and one-time UW Husky Andrew Kittredge is making his AAA debut. DJ Mitchell elected to become a free agent after he was DFAd to make room for Endy Chavez.