What’s Past is Prologue…Maybe

In one of the least heralded of his latest flurry of transactions, the M’s picked up right-handed reliever Shawn Armstrong from the Cleveland Indians in exchange for some of the international bonus pool spending authority they’d accumulated to try and sign Shohei Otani. Armstrong has never started, and though he bounced around the fringes of the Indians’ top 20 list, the sense that he was destined for middle relief limited his appeal as a real prospect. He’s now out of options, a fact that may see him signed/released by several teams in the next few months.

Armstrong’s thrown 43+ innings in three separate stints with the Tribe, accumulating zero runs above replacement. Do projection systems see untapped potential here? Er, no, they see a guy who’s been replacement-level and project him as…replacement level. There’s nothing really shocking here, despite some gaudy AAA strikeout rates. Those haven’t quite translated to the big leagues, and his walk rates are scary, and, perhaps most importantly, big league relievers – as a group – are really, really good now. You don’t look at Armstrong’s Fangraphs page and see someone likely to help immediately. And since he’s out of options, you *also* don’t see a project who might work something out in Tacoma.

This blog, at its core, has been organized around the idea that the right statistics give us some insight into a pitcher’s talent, and that a pitcher’s results are, given a decent sample, related to that talent. Variance/luck/etc. will result in some mismatches between talent and results, and again, that’s where the stats can be valuable – they can aid in identifying undervalued players. In the main, on average, this theory works pretty well. A great pitcher whose results are sullied by a freakishly high BABIP will likely post better results down the road. Individual players can change, and the very phrase “true talent” almost implies something immutable or fixed, something that’s not true at all. But every game post, I’m looking at, say, pitch fx data or FIP or something other than a guy’s W/L record, or how’s he’s fared against AL West teams on Tuesday nights, because those numbers give us some sense of what we’re going to see. If you look at Shawn Armstrong’s numbers, you’re not encouraged. If past is prologue, then Armstrong will cycle through a bunch of teams as he’s waived, and will eventually sign a minor league deal with an opt-out.

But Armstrong looks…familiar. Here’s a table featuring one of the ol’ stand-by blogging devices – my apologies, it’s December and I’m not feeling creative at all:

| FB Spin | FB Vert. Movement | FB Horiz. Movement | Cutter Spin | Cutter Vert. Movement | Cutter Horiz. Movement | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Player A | 2396 | 9.28 | -3.71 | 2483 | 5.78 | 1.37 |

| Player B | 2363 | 9.3 | -2.82 | 2486 | 4.83 | 1.21 |

Player A throws a four-seam fastball with 2396 RPM spin, while Player B’s at 2363. For context, the league average value last season was 2255; 632 players threw at least 25 four-seamers (including Chris Gimenez? Really?), and so both A and B are solidly in the top 3rd in spin rate. Movement-wise, the pitches are even more freakishly similar – just 2 hundreths of an inch difference in vertical rise, and less than an inch in horizontal break (there’s very little of it from either hurler). They both throw cutter/slider things, and both are thrown hard (meaning thrown at a velocity close to their fastball), and with a bit of cut and sink. These cutters have high spin rates as well; the league average is 2344, and A and B are next to each other on the spin rate leaderboards (in the top 1/4th). High spin fastball and high spin cutter – if you thought “Nick Vincent” congratulations, he’s Player A. B is Armstrong. Remember that Vincent was signed when HE was out of options and could’ve been waived by the Padres. Vincent had had much more big league success, but was essentially freely-available back before the 2016 season.

Vincent never threw as hard as Armstrong, but – and I’d actually forgotten this – used his cutter and fastballs to dominate righties. Lefties ate him alive, but he really controlled righties, which is something I wrote about when the M’s picked him up. With the M’s, Vincent’s shown essentially no platoon splits, and has handled lefties remarkably well. Vincent and the M’s took something that was a part of his statistical record and changed it. It’s still too early to say definitively whether this is variation or if his “true talent” changed, but the M’s got two solid years out of Vincent – two years in which he’s been dominant against lefties, a fact that’s enabled him to pitch in higher leverage situations and to face more batters than anyone relying on his fangraphs page would’ve expected. I’ve beaten the M’s up these past two years for their mediocre record in player development and their inability to keep players around long enough to try, but Vincent’s a – maybe THE – example of a clear-cut developmental success.

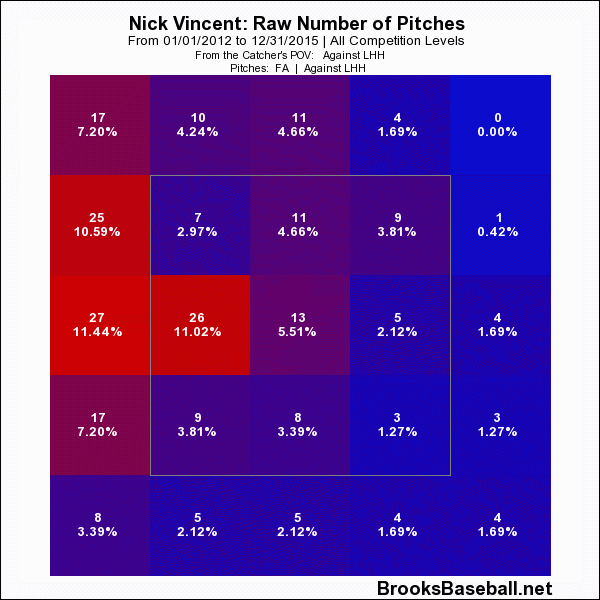

One of the keys has been how Vincent attacks lefties, something Jerry Dipoto talked about with regard to Juan Nicasio in the last Wheelhouse podcast. Here’s where Vincent spotted his fastball against lefties with the Padres:

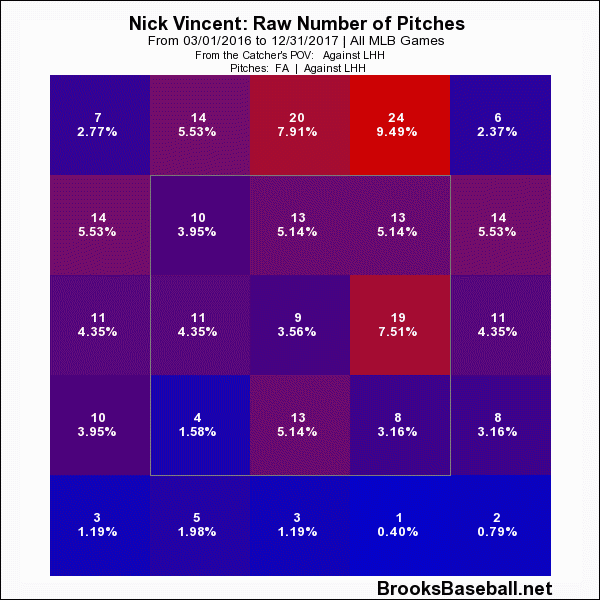

This usage reflects a pretty common idea: righties should keep fastballs away from lefties – or righties, for that matter. It’s harder to pull them, after all, and thus harder to drive. Vincent threw his fastballs up and middle-away to righties, and away to lefties. It worked against righties, and didn’t work at all against lefties. What’s he done with the Mariners?

There’s no longer a clear difference in how he attacks lefties and righties: both get elevated four-seam fastballs, and lefties are now more likely to see an *inside* fastball than an away version. To understand why the M’s might prefer this approach, we’ll go back to the Wheelhouse podcast and Jerry’s discussion of “effective velocity” in episode 2. Here, they’re not referring to the effective velocity measurement in statcast, which accounts for a pitcher’s stride toward the plate. Instead, he’s referring to Perry Husband’s concept. A hitter needs less time to get his bat to an away fastball than he does to an inside fastball. A down and away fastball isn’t worthless, but because a batter can react later to it, it makes the pitch seem slower – a batter needs less time to put that pitch in play than a fastball with the exact same velocity thrown inside. Vincent stopped turning his 89-MPH heater into an effectively-86-MPH heater, and became an all-around reliever.

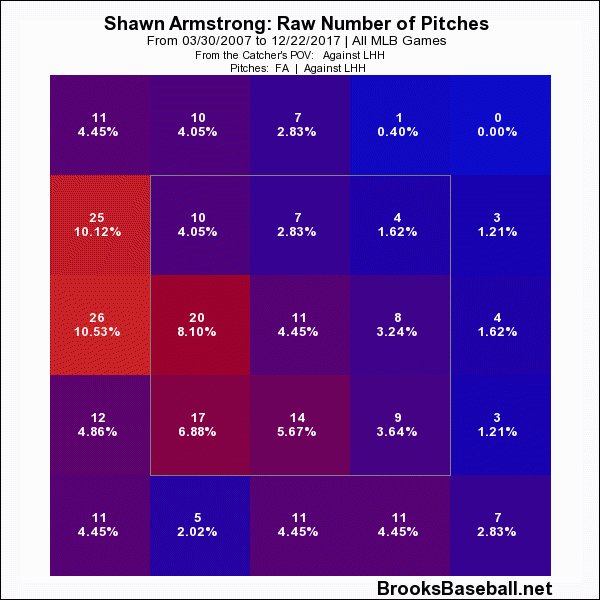

You probably know where this is going. Here’s Shawn Armstrong’s fastball usage to lefties:

Armstrong hasn’t had the same trouble with lefties in the bigs, but then, he’s not exactly maximizing his effective velocity to righties, either. And it’s righties who’ve absolutely killed his fastball. Armstrong is very, very similar in many ways to Vincent, and Vincent has completely changed his approach since he got here, making him a much more effective pitcher overall. It’s possible Armstrong could break free of his statistically-inferred true talent, too, and by following the same general change in approach.

The more I’ve written on this statistically-obsessed blog, the more I’ve come to the idea that it’s these critical shifts in “true talent” are what drive team success. Critics sneer that sabermetrics turns real flesh-and-blood players into trend lines and probability stats, and while that’s grossly oversimplified, there’s…there’s something there. What’s the alternative, shout aggrieved saber-wonks? Rely on how a player looks in uniform? Go by draft order? I’m going to stick to the stats, personally, but I’ll say this: the most important thing the M’s need to do is to have a few of their players make their past statistics utterly irrelevant. Jean Segura did this with Arizona, of course, and Nelson Cruz didn’t become a different player, but became a vastly *better* version of himself in his mid-30s. On paper, this M’s team lacks the talent to compete with either the Astros or Angels. It doesn’t sound like the M’s are going to materially change their talent level between now and April. Ergo, the M’s need to fundamentally change the talent of the guys they already have.

Heading into 2014, Jose Altuve had played 2.5 seasons of perfectly fine baseball. If he was remarkable, it was due to his comically small stature, and the fact that he’d come from nowhere to become a starting player on a team that pretty clearly valued him for his minimal paycheck. In 2014, Altuve had his best season, one that seemed like the logical peak for someone with his (powerless) skillset. A nice BABIP pushed his average way up, and thus Altuve was valuable. Since *then*, however, Altuve’s become something unrecognizable, and something much, much more dangerous. After racking up 21 HRs in his first 3.5 MLB seasons, he’s hit 24 in EACH of the past two. Jose Altuve just slugged .547 on his way to a well-deserved MVP award. Carlos Correa is amazing. #1 draft picks are great, and offer unbelievable talent. Altuve was an afterthought, and then a stopgap, and then a force. No one looking at either Jose Altuve or Jose Altuve’s stats would’ve projected this, but there it is.

You may have seen the photo of Tim Lincecum training about 50 miles north of here at Driveline that’s flown around Baseball Twitter. The great Patrick Dubuque wrote about it at BP here, and he’s right – Lincecum doesn’t *need* to do anything more. His career – his meteoric rise to the top of baseball – was enough, and he has nothing left to prove. We all saw Lincecum’s last appearance in the bigs, pitching for the Angels, in what’s sure to be a tough pub quiz question 10 years hence. He pitched 3+ IP against Seattle, giving up 6 runs on 9 hits, and with an ERA standing at over 9, the Angels released him after that day in August of 2016. The statistical record looks pretty damning: declining velo leading to worse and worse results, and there you go – an early peak, an early fall, and hey, pitchers, amirite? As we’ve seen so often, though, players have much, much more control over their true talent than people like me ever imagined. Does this mean Lincecum’s back? Is Shawn Armstrong the next Nick Vincent? Will Ben Gamel hit 30 HRs? I don’t know, I don’t know, and I doubt it. But if I could make the M’s better than their rivals at any aspect of running a team, it’d be this ability to make a player unrecognizable – to blow the trend and the carefully-constructed scouting report out of the water. The Astros did this with a number of players, and that ultimately meant more to their World Series win than drafting Carlos Correa (though for the record, I’d like the M’s to draft the next Carlos Correa). The M’s trail the Astros in talent, and they need an out-of-nowhere leap in ability from a few of their players. That’d make a fine Christmas gift.

Comments

2 Responses to “What’s Past is Prologue…Maybe”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Marc, you may not be feeling creative, but this is a brilliant and fascinating piece. Now, I’m very interested to watch Armstrong pitch. Maybe we’ll get a Tim Lincecum watch too?

Dipoto suggested that Armstrong may not stick around. Given the fact that he’s out of options and they’re stacked with relievers right now, it wouldn’t be shocking to see him flipped.

It’s going to be interesting to see what the hell they do with this oddball mix of starting pitchers with limitations, relievers, and young first basemen. My best guess is that we’ll see another reliever or two traded.