Bugs Bunny, greatest banned player ever

Update 2/21: I found out today from Glenn Stout, the series editor, this has been selected for the 2007 Best American Sportswriting annual! Woo! This makes USSM the first blog and the first non-ESPN.com/Slate site to be so honored.

With the DVD release of "Looney Tunes Golden Collection" it is at last possible for us to examine in detail one of the most famous baseball games ever played, and see what lessons the contest holds for the analytical community.

"Baseball Bugs" (1946) depicts a game held at the Polo Grounds. No date is given, but artifacts shown such as public address equipment and advertisements ("Filboid Studge," "Nox, 2 for 25," "Manza Champagne") definitively place it during the 1946 season. The visiting Gas House Gorillas are playing against the home team, the Tea Totallers. It is a day game and conditions are good.

The first view of the scoreboard shows the Gorillas at 94 runs (10-28-16-40) after the first four innings. This appears to be footage inserted out of order, as we’ll determine later the score then was not 96-0 but rather 54-0. While obviously neither team was a major league affiliate and it is almost certain that the game played is an exhibition, the score is already notable. The total of 54 runs was far more than the previous all-time run scoring record for a team in a game (held by the Chicago Colts, who scored 36 against Louisville in a game on June 29th, 1897), and the score of forty runs in an inning would be significantly above the most runs scored by any inning by one team (18, by the Chicago Colts in the 7th inning on April 14th, 1883).

The stadium is entirely filled, and as we know that the Polo Grounds could hold 55,000 fans in that year’s configuration, it is fair to assume that this was a game of some note, and that the players participating were extremely popular.

We open to see "a screaming liner" hit by the home team. The outcome of the hit is not defined, and the hit itself seems an indicator that the game was not official: the ball appears to be a shade of grey, and makes an almost-human screaming noise as it travels, neither of which was normal behavior for a regulation baseball in play. Since the balls used in the remainder of the game are white, and since we also see that the Teatotallers are a horrible offensive team, it is reasonable to conclude that this footage is from some kind of pre-game hitting contest, or perhaps an entirely different game.

The initial comparison of the teams’s players offers a startling contrast, as well as a further confirmation that this is not an official game. In 1946, baseball was in transition. During the first half of the decade, as the equipment and personnel needs of the war took precedence, baseball had become a slap-and-dash game, characterized by little hitting and little power, but with many stolen bases. After the war’s end, with returning players came plate discipline and power hitting, and almost all of the wartime players were quickly forced out.

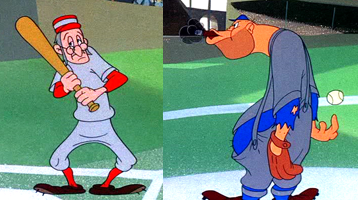

This is obvious even in the first shot of the Gorillas pitcher as compared to the Teatotaller. Both wear uniforms without a team name, number, or other identifying characteristics, but they otherwise could not be more different:

Illustration 1: A visual comparison of players

I have summarized major differences in Table 1.

|

Characteristic |

Gorilla pitcher |

Teatotaller batter |

|

Height |

Over 6" |

Apx 5’5" |

|

Weight |

Over 220 lbs |

Under 125 lbs |

|

Uniform colors |

Dark grey and blue |

Light grey and red |

|

Eyeglasses |

No |

Yes |

|

Grey hair |

No |

Yes |

|

Illegally ragged uniform |

Yes |

No |

|

Visible facial hair |

Stubble |

Sideburns |

|

Slouching |

Yes |

No |

|

Smoking cigar while playing |

Yes |

No |

Table 1: A comparison of characteristics of players

The Teatotaller identifies himself as being "Ninety-three and a half years old". It is unclear whether this is a humorous exaggeration by the player, but he is extremely slow to swing and awkward, as if once he has put the bat in motion he is unable to control it effectively. Clues offered from his appearance and analysis of other Teatotaller’s biomechanics, in particular their posture and stylistic hitches in their method of play, suggest that no one on the team is under fifty. While today this seems only a little odd, we should remember that modern nutrition, training, and medical support allow players much longer and more productive careers. In 1946, there were few players forty or older: three in the National League, and the oldest player in either league was Ted Lyons at 45, pitching in only five games.

You can also see that the Gorillas’ catcher wears no facial protection of any kind, even turning his hat around. This brash display of fearlessness must certainly have been intimidating to the other team, given their age-related susceptibility to broken bones if hit by a ball.

This raises a series of troubling questions I admit that I cannot answer, either in viewing the game or in subsequent attempts to research it using primary sources:

- Why would a team of extremely strong, young men play a game against a team of extremely old, weak men?

- Why would over fifty thousand people attend such a game?

The second pitch of the game is quite high, and the Teatotaller does not swing. It’s initially called a ball, but the Gorilla catcher (who, like his teammate, is extremely large) hits the umpire on the head, driving him fully into the ground. The umpire apologizes profusely and changes his call to a strike.

While it is tempting to look at this as part of the long history of player-umpire violence, instead consider this as a demonstration of the raw power of the Gorillas’ catcher. Given the coloration and quantity of the dirt displaced in the act, it is clear that the area behind home plate is extremely loosely packed matter, such as sawdust, possibly mixed with sand.

Illustration 2: Modest soil displacement

A further limitation to the force of the blow is the survival of the umpire. At first the umpire is able to respond in an apologetic manner on realizing his error. The umpire then passes out, presumably with a concussion. However, the history of head trauma injuries is filled with strange tales of lucidity after horrible injury, and this is no less believable than what many trauma rooms see on a daily basis. A presence of an umpire at home later is inconclusive in establishing the struck umpire’s survival or replacement.

And yet, even given those caveats and boundaries on how great the force must have been, the amount of acceleration applied to the umpire so suddenly, and without noticeably harming the catcher at all, testifies to the physical condition and hardiness of the Gorilla players.

When the Gorillas are up to bat again, we see for the first time the ineffectiveness of the Teatotallers’ pitching. An frail elderly gentleman with long sideburns that swing during his delivery throws a slow, overhand pitch which is hit directly at him. Gorrilla players are shown walking to the plate, getting a hit on the first pitch, and immediately starting towards first as the next player steps up without even waiting for the previous batter to reach first. The traumatized pitcher continues to throw, and each pitch is hit smartly at him, causing him to duck. This occurs three times.

At one point, we are able to see over thirty Gorillas circling the bases, so close that they actually put their hands on the person in front of them and form a conga line as they walk around the bases, careful not to pass the person in front of them, for fear they will be called out for advancing in front of the previous runner. That there are over thirty tells us several things:

- The teams playing were allowed to carry a full major league roster

- In the carnage, even the Gorilla coaches, bat boys, and other uniformed staff were able to bat and hit against the weak pitching, and neither the Teatotallers or the umpires noticed this and called the illegal batters out

It’s a further testament to the addled mental condition of the Teatotallers during this drubbing that they were unable to take advantage of the congested baserunning by fielding any ball and throwing it to any base, where it would have immediately forced out three runners and ended the inning.

Illustration 3: Gorillas round the bases

A shot displays a rapidly changing score of 42 runs in that inning so far. This shot establishes an scoreboard discrepancy that is not noted anywhere else or in contemporary accounts. Early on, before the Tea Totallers bat, we are shown a scoreboard:

|

Gas-House Gorillas |

10 |

28 |

16 |

40 |

|

Tea Totallers |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Table 2: Scoreboard as initially displayed

After which the Tea-Totallers bat and do not score. Then, in this, the conga-line inning, the scoreboard is shown as

|

Gas-House Gorillas |

10 |

28 |

16 |

40* |

|

Tea Totallers |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Table 3: Scoreboard as displayed the second time

*increasing to 41 and 42

During the short footage of the Gorillas circling the bases, we see several hitters cross the plate. There are several possible explanations:

- The home team scoreboard operator decided to re-start the fifth inning as the fourth, given that the fifth had gone so badly for his team, and we happen to see the Gorillas pass the 40-run mark a second time. This is ruled out, however, by the presence of the crowd and the fact that it is still day. Even though we can see that the Gorillas are agressive batters and swing early at pitches, and that the Teatotallers are inept hitters, the sheer amount of time it would take to play a 134-run game (to that point) makes this unlikely. This is supported by analysis of game lighting: given the lack of discernable shadows but with a well-illuminated park, we can tell that the game was played either at mid-day under light cloud cover, or at dusk. Later events (specifically the extended Bunny comeback) rule out the latter.

- The earlier shot is an accident, an insert of footage taken later. While we can determine that everything else is in chronological order, it is the most likely of the explanations and the one we’ll accept here.

There is an important lesson from this inning: run scoring is not dependent on taking walks or even on seeing a lot of pitches. The Gorillas score 42 runs in this inning alone by drilling single after single right at the pitcher. By keeping the pace of the game extremely fast, they kept the pitcher in the game, presumably because he had a low pitch count and was not tired, but also there was no pitcher warmed up to relieve him, and the Gorillas scored so quickly that they drove the score up before one could even be told to begin stretching. There is an additional psychological effect to be considered, as well: faced with a team that can score 42 runs in an inning, the opposing manager must have been so stunned by the offensive onslaught that he was unable to make a move, and further that his coaches and other staff were similarly disabled. It would be difficult to apply this advantage in a game situation, but is a situation worth watching for because once gained, it can clearly be exploited to great gain.

We are then introduced to the shabby state of both the grounds keeping and of stadium security at the Polo Grounds, as we see an angry rabbit (Bugs Bunny, RHP/UT) is able to heckle the visiting team from left field, where he has dug a fairly substantial hole, and is enjoying a carrot-dog and (it appears) has consumed a large bottle of wine through a straw.

Illustration 4: Evidence of lax security and groundskeeping

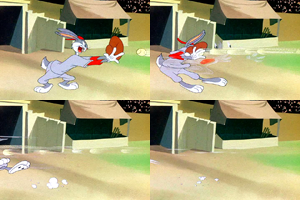

The Gorillas, presumably bored at the level of competition offered at the game, force Teatotallers equipment upon the rabbit and he enters the game. The new lineup is announced:

C: Bugs Bunny

LF: Bugs Bunny

RF: Bugs Bunny

P: Bugs Bunny

3B: Bugs Bunny

CF: Bugs Bunny

1B: Bugs Bunny

SS: Bugs Bunny

2B: Bugs Bunny

Using an orthodox delivery, Bugs delivers a pitch which appears quite fast, but is then able to take the catcher’s position and (as the catcher) encourage himself (as the pitcher). When he catches the ball, the force of the impact throws him back and shatters the backstop.

Illustration 5: Impact of highly acclerated ball on catcher

This provokes a most interesting investigation. Clearly, the ball cannot have been thrown with much force, or he would not have been able to have run and caught it. We can be especially sure of this given that catching the ball imparted far more force than he could have expended throwing it. However, from what we can see from the ball’s path as it is caught is that it is nearly flat and extremely fast. Relativity prevents us from believing that he is able to travel and nearly-luminal speeds, as it rules out traveling extremely fast and arriving three-seconds before the ball without (as one barrier) himself experiencing massive and noticeable aging.

What can we make of this then? Two theories appear initially viable:

- There is a wormhole as theorized by Feynman and others that allows Bugs to step off the mound and be transported back just slightly in time and over about sixty feet in distance without affecting anything else

- Bugs’ delivery of the pitch is deceptive, and it is actually extremely slowly thrown with respect to the plate, and it is his encouragement of the pitch that acclerates the ball towards the plate, "flattening" its trajectory

When thrown, the pitch must be traveling at least as slow as 15ft/s (to give him time to run to the plate and then talk). At the same time, it can’t touch the ground before crossing the plate, or be ruled an automatic ball, so it must actually be thrown upwards at least as fast as to resist the force of gravity (as g =32ft/s^2). Since the pitch crosses the plate at approximately the same height it was thrown, we know when it left Bunny’s hand, it was traveling at about 64ft/s. Neglecting air friction and the effects of spin on the ball:

0s: 64ft/s up

1s: 32ft/s up

2s: 0ft/s up

3s: 32ft/s down

4s: 64ft/s down

64ft/s = 3,840ft/m = 230,400 ft/h = ~44mph

Therefore, he throws the pitch in the air at about 44mph and possibly quite slightly towards home. In the time the toss gives him behind the plate, he begins to chatter. In his three seconds of yelling, he’s able to cause the ball to accelerate extremely fast. We can estimate the speed of the ball given the force applied to Bugs while catching it. If, as seems reasonable, we figure he weighs 80lbs, the force to throw him directly into the backstop and do significant structural damage to that backstop can be estimated ("Estimation of pitch speed through re-creation of secondary observations using weighted mannequin and riot suppresion weapons," Zumsteg, 2004). We are able to figure that the pitch was traveling at least 150mph and possibly much faster.

That means that Bunny was able to cause the ball to accelerate by at least 50mph/s^2. Based on these calculations, it would seem possible for Bunny to actually fly and even to achieve escape velocity and orbit the planet using only his heckling. However, it’s important to note that as demonstrated in this game, we can only definitely establish from the footage that he is able to perform the acceleration when drawing an object to him, and only on the baseball. Even if we consider that this demonstration is the only time this happens, it still raises other questions:

- How is this possible?

- Why doesn’t Bunny throw a ball and then from the mound encourage it back as the batter swings?

- Why doesn’t Bunny use this ability on batted balls as a fielder, drawing balls to him for easy outs?

The possibility that it can only be done while crouching does not rule out either of those uses. It may be that this acceleration through encouragement can only be done while catching, a theory that is supported by circumstantial evidence, but particularly by the fact that if such an effect were available to him, there is no reason he would not use it then. As to the last question, as we’ll see later, circumstantial evidence seems to indicate that he does do this, even if the effect is not shown. The issue warrants further investigation.

Almost as baffling is Bunny’s "slow ball". Traveling a straight line and barely rotating, it moves so little that three batters take three swings at it and never make contact. Given the ball’s extremely minimal rotation, it seems likely that this is not a "slow ball" as we conventionally think of it but instead a knuckleball, which Bunny is using to best take advantage of the known unusual air currents at the Polo Grounds. If we acknowledge that it was a knuckleball, the hitters’ inability to make contact becomes much easier to explain.

Bunny’s innovation extends to more than possible new discoveries about physics and the nature of perception. In his first hit, Bunny attempts to score an inside-the-park home run but finds a Gorilla covering home plate has received the ball. Bunny then shows him a pin-up of (we must believe) surpassing attractiveness, causing the player to go into fits of pleasure. This allows Bunny to score easily. If such beauty is indeed usable (and use of it does not violate the rules) and can be reliably applied, this is a clear innovation with applications in fields as diverse as anesthesia and crowd control.

Illustration 6: Effect of displaying pinup to Gorillas catcher during close play at home

Bunny scores, and we are given our first shot of the new scoreboard. Interestingly, the Gas-House Gorillas are now the home team. Bunny inherits the first four (see above) innings of scoreless Teatotaller play, while the Gorillas now lead by 96-1. This seems to indicate that the Gorillas, after impressing Bugs to play against them, gave up on that inning. It is not clear why the sides switched, though earlier cheering for the Gorillas seems to indicate wide local support, or why Bunny was forced to substitute in and inherit the score if he replaced the entire opposing team and switched from home to visitor.

In a tense confrontation at home, we see the Gorillas replace the umpire by force with one of their own so that they can call Bunny out at home in the next play. Bunny, to his credit, then manages to argue the fake umpire into reversing his own call. It is a rare application of mental acuity and misdirection in debate that persuaded the umpire to change the call – against the interests of his own team – and allowed Bunny to score again. For those that say that arguing with umpires is guaranteed not to help and is frequently harmful, this will stand as a powerful counter-example. If a player impersonating an ump can be turned to reverse a call in those circumstances, what chance does a neutral arbitrator have against a similarly golden-tongued player? We can only hope that a real umpire, faced with the same kind of oratory jujitsu, would have the presence of mind to focus on the events and continue to make the right call.

Illustration 7: Bunny argues his case with ursurper umpire

We are then shown a disturbing fielding play. A Gorilla, chasing down a line drive hit by Bunny, catches it and is knocked backwards and down into the turf, where he burrows into the ground and disturbs a headstone to appear, bearing the words "He Got It".

Illustration 8: Effect of highly-accelerated ball on outfielder

While this Gorillas player is much slighter than previous players shown, that a ball could impart that much force seems implausible. For one, a ball traveling so fast would have reached him much quicker, and appeared to be traveling much "straighter" than the one we see. Further, such a ball would not have been caught, but instead would have shattered the player’s arm and broken through the glove and proceeded to bore through the player’s body. That it does not offers us a possible solution: that players, by shouting at the ball or otherwise, are able to dramatically accelerate it. The outfielder, either not observing or not understanding this apparently temporary phenomena, was responsible for drawing a ball towards himself, each shout adding to its velocity, until, fatally, he caught it and, unlike Bunny, was unprepared for an impact of such force.

But then how is he able to catch the ball safely and still be driven into the ground? The only plausible explanation is that on catch, the ball continues to accelerate even though the player is no longer shouting. Further evidence that ball behavior is divorced from fielder vocalization comes quickly. On the next hit, Bunny’s line drive is able to drive a different Gorilla approximately ten yards into a tobacco advertisement on the outfield wall. This player says nothing in fielding, and so disproves that fielder shouting is the cause.

This would further support the contention that it is Bunny who has a singular ability to accelerate the ball, and that this ability is not limited to catching or to only drawing objects to him.

Catching: while waiting for a pitch, is able to yell and cause the ball to accelerate towards him

Batting: yells before receiving the pitch, able to hit the ball and then cause it to accelerate equally after contact.

Alternately, we can consider that the mass of the ball is not constant, and Bunny is somehow able to alter or control both the speed and mass of a ball in play to provide beneficial results.

As to the matter of the tombstone, there is no other contemporary or historical account of that incarnation of the Polo Grounds being built on a graveyard. This should be attributed to an unlikely grim coincidence.

Bunny’s ability to control energy is further demonstrated on a play when, faced with an unconventional defensive alignment in which all nine Gorillas form up off the third base line, is able to hit all nine of them with a batted ball, maintaining the ball’s speed. Each struck fielder lights up, showing a yellow luminescence characteristic of electrical discharges.

Illustration 9: Effect of highly-charged ball impact on Gorilla fielders

This electrical discharge causes the scoreboard to display random colored numbers and text ("TILTED").

We are shown only one other play, in which Bunny tags a Gorillas player out so forcefully that the runner hallucinates.

We next learn that Bunny has taken the lead, 96-95. This means that at some point during the game, the official scorer ruled at least one of the Gorillas’ runs invalid, as we had previously established that they had scored 96 runs when Bunny took over for the Teatotallers. The cause and resolution of the disputed run is not documented in available footage.

The game situation as announced is 2 outs, bottom of the ninth (as the Gorillas are now the home team, they are at bat), with one baserunner. The batter chops a tree down to use as a bat measuring approximately 20 feet long and three feet in diameter, affording the hitter plate coverage unequalled in the history of baseball.

Illustration 10: Largest bat known to have been used in a baseball game

Assuming that the tree is of a normal variety and not, say, balsa (what little observation we can do from the footage does rule out exotic and lightweight trees), we can calculate the weight of this bat as

Volume * (weight/cubic foot)

Using a generic weight for the wood of 35 pounds per cubic foot, I estimate the weight of the bat at just shy of 5,000 pounds, including handle. Even if that the bat was corked (how this would be accomplished in the time available is unclear), it would still weigh thousands of pounds. That the Gorillas hitter is able to swing this massive tree indicates that Bunny is not the only player on the field with extraordinary powers.

Bunny attempts a "called shot" of pitching, asking the fans to "Watch me paste this pathetic palooka with a powerful, paralyzing, perfect, pachydermous percussion pitch."

It is notable that, while appearing to be fast, this pitch is hit extremely well by the Gorillas hitter. It is unlikely that any pitch could avoid contact with a bat of that size if the batter was able to time his swing remotely well. Consider that even an extremely early or late swing would still put wood to the ball, due to the length of the bat. If the ball’s trajectory is straight and it does not hit the ground, even a 6 degree swing (rather than a 90 degree one, bringing the bat perpendicular to the batter’s foot position) would still allow the bat to make contact (approximately twenty feet behind the plate). Note that such contact would result in a foul ball unless it hit a knot or other irregularity in the bat.

The batter takes a full swing and the ball is hit out of the Polo Grounds. Bunny attempts to pursue the ball in a taxi, but is foiled when his driver turns out to be a member of the Gorillas – that he has a taxi license with his picture on it further supports the earlier contention that the Gorillas are not a professional team, though it makes the question of why fans turned out in such numbers even more baffling if the players were not professionals.

Bunny leaves the taxi and is lucky enough to catch a bus, which delivers him to the Umpire State Building. After taking an elevator to the top, Bunny hoists himself up a flagpole and throws his glove up. The glove then moves to catch the passing ball and returns to Bunny’s hand. Fortunately, an umpire was scaling the building exterior, possibly with the intent of suicide arisen from shame over being removed from the game by a contestant. The umpire is able to make the out call, thus ending the game. Note that in major league games, throwing equipment at a ball is not legal, but at this point we have firmly established that the game is not played under the rules of major league baseball and should not regard this ruling as aberrant. The call so disturbs a Gorillas player that he begins to hallucinate that he’s being taunted by both the Statue of Liberty and Bunny.

What can modern baseball analysis tell us about the talent of Bugs Bunny? Unfortunately, we are faced with several problems:

- This game provides us with an extremely limited sample. Bunny plays for only five innings.

- The level of competition is never established.

As the first can’t be overcome, let’s deal with the second. From the level of fan interest, it is fair to assume that the players involved are good enough to be a major draw: a semi-pro game of local celebrities would not (and still does not) draw a sufficent crowd to pack in fifty thousand fans who cheer wildly at events (for one example, see the attendence at MLB All-Star Celebrity Softball games). The best-fit explanation is that the Teahouse Totallers are a collection of former greats of baseball, playing against a team of current pro and semi-pro players drawn from the New York region. This seems to fit available player data, as well. For instance, New York Giants player Johnny Mize was 6’2" and 215 pounds, and a good match for several of the leaner Gorillas players seen, though he bats left-handed, and we do not witness "The Big Cat" or any left hander take a swing either against the Teatotallers or Bunny. Given the age of the Teatotallers, we can safely assume that they are greats of pre-war baseball.

Using modern projection estimation engines, it is possible to guess at the current talent level of the Teatotallers at the time of the game, given their level of performance when forced out of baseball and then again, fifteen to twenty years later, playing an exhibition game at fifty and over. While we must of course look at any results with a great deal of skepticism, as there is little data on the effects of aging deep into later life, even the extrapoloation of existing known trends (reduction in bat speed, fielding ability, and so on) provided startling results. Even a team of the greatest players who had retired in the late 1930s would have been poor competition for a regional unaffiliated professional team, or for a modern equivalent, a short-season rookie team (such as the Pioneer League).

At the same time, given what we know about the physical characteristics of the Gashouse Gorillas, we can match them up with similar players from the time, favoring players on local teams. Assuming a mix of at least 50% local players not affiliated with a major league team, we find that the Gorillas were quite close to major league-quality, with a difficulty adjustment of about .900 compared to the major leagues. As a point of comparison, the highest minor league level has a difficulty rating of about .850 in any season. It is worth noting that given the projected roster, they were an extremely poor defensive team. Still, the Gashouse Gorillas, even as composed, were nearly major-league quality, and facing a team that have have once been good, but was of nearly no present quality.

Why such a game would be scheduled remains unclear. Efforts to find contemporary promotional material for insight into fan motivation or how the game was marketed have proved fruitless.

If we accept that definition of the Gorillas’ level, then the performance of Bunny becomes even more astounding but measurable. While complete stats are not available, we know that he shut out the Gorillas for five innings, when we would expect them to score over two runs against another team. Bunny did this, however, without any defense behind him. Every play had to be made by one player, which interestingly offers us a way out of recent arguments about how much a pitcher contributes to the outcome of balls put into play. With the exception of luck, all factors thought to have a significant effect are here the responsibility of Bunny. While we see him strike out three batters, the actual events matter little. If he struck out the remaining ten batters we do not see, he makes what must be spectacular plays defensively. Either his pitching or his defense are exceptional, and quite likely both.

Bunny’s line for outcomes we see: 1.6 IP, 0 R, 0H, 3K, 0 BB, 0 HR

It’s clear that as a pitcher and fielder, Bunny excelled in those five innings, holding scoreless a team that would have been good compared to other major league teams. Even assuming that the knuckleball can rarely strike out three batters at once, this demands further inquiry. The limitations of reasonable (or even possible) fielding ability imply that Bunny must have been extremely good at getting strikeouts or that he was able to use his previously-established ability to accelerate balls towards him to turn balls in play into easy outs.

While there is no evidence Bunny played in other exhibition games or unsanctioned leagues for which there are records, it is possible that he played under an assumed name. Further investigation may allow us to better deliniate how much of his success was in fielding and how much in pitching.

As a hitter, the feat is even more astonishing. We see no evidence that he was allowed courtesy runners, and yet he scored 96 runs. This implies 96 home runs, either inside the park or by hitting the ball over the outfield fence. Given his displayed speed and the Gorillas’ almost certain poor defense, along with his ability to improvise when the situation turned against him, Bunny took advantage of circumstances that allowed him to use his talents to take advantage of the other team in an unprecedented display of offensive prowess.

Consider that given fifteen outs, Bunny scored 96 times. His RC/27 would be 173. Now of course Bunny could not always face a team so ill-equipped to deal with his high-percentage take-all-four-bases running style and bean-all-nine-fielders hitting ability, but even dramatic penalties placed on him would still make him the greatest offensive player of all time.

But this is all speculation based on incomplete footage of an exhibition game. It is a shame that we will never know how good Bunny might truly have been, and that there is but one record of his exploits on the field.

The exclusion of non-human players like Bunny is another shameful example of the long history of injustices done by baseball’s racist policies. That black and rabbit players could only play against white players in non-sanctioned exhibition matches deprived the game of some of the best talent to ever play, and from what we’ve seen, robbed scientists of a chance to better study phenonema with wide applicability to questions of physics that could have greatly benefited all residents of the earth, be they human or Leporidae.

Comments

67 Responses to “Bugs Bunny, greatest banned player ever”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Hate to be contradictory, but this is just another illustration of the irrational front office/fan love-a-thon with all things Bunny. If WFBunny didn’t have the floppy ears and snappy wisecracks, we would see him for what he really is: Just another replacement-level rabbit who happened to play every position.

And don’t get me started on small sample size . . . he was dominant for half of a single game in what was clearly a pre-steroid era.

[…] MSN Sports Filter Okay, this has been linked to all over the ever-lovin’ Web in the last day or so. But on the off chance you ain’t read it yet, here it is: a sabermetric, sociohistorical investigation of the 1946 game between the Gas House Gorillas and the Tea Totallers, as captured in the immortal Warner Bros. cartoon "Baseball Bugs".  I’ve said it before, and say it again I shall. If you can’t get into Bugs Bunny, I don’t care to know ya.  Thanks to The Bro for pointing this my way. […]

[…] An analysis of the greatest baseball player of all time. […]

[…] U.S.S. Mariner » Bugs Bunny, greatest banned player ever This just blew me away. […]

I was a 15 year old baseball fanatic in 1946 and would have known about and remembered this game if it had been played at the Polo Grounds in front of 55,000 fans. I don’t think this game actually happened. I think the whole thing was just made up.

[…] Now Dave at the USS Mariner has given us the Looney Tunes version – a long, smart and knowledgable analysis of one baseball game upon which Bugs Bunny brought his inestimable gifts. […]

I registered just to congratulate the author on this; Melville must have had too much time on his hands when he wrote Moby Dick too, so you’re in great company.

Someone might want to send this to the tedious William Safire over at the NYT Magazine; a few months ago, in his grammar and usage police column, he cited the Bugs Bunny Change Up, and said the name came from the legendary contest between the tortoise and the hare. What a dink! Anyway, apparently hundreds of us emailed him with the correction that it came from this cartoon, and he was forced to acknowledge his error in print. But out of the literally hundreds of replies he received, he thanked one person for setting him straight: A NEUROPHYSICIST FROM STANFORD!! God forbid he admit he learned anything from a cab driver or billing clerk…

For my two cents, I believe the Gashouse Gorillas are the St. Louis Cardinals, weren’t they the Gashouse Gang??? And I THINK I have a dim memory of someone explaining to me long ago that the Tea Totallers were a jab at a team who had a player that was some holier-than-thou Prohibitionist…

And one other thing…the electrical discharge thing, and the scoreboard going nuts and proclaiming TILT? The whole thing is supposed to be a pinball machine, that’s what happened when you pushed a pinball machine to the max, it tilted and the control panel went kablooie…you kids…..anyway, my congrats again, this is a stitch.

PPaige asked if the St. Louis Cardinals were known as the Gas House Gang and could have been the prototype for the Gas House Gorillas. In fact the Cards were known as the Gas House Gang and cultivated their image as a rough and tumble baseball team. For example,they deliberately did not always wash their uniforms between games and started some games with dirt smeared uniforms. They had colorful players like Pepper Martin at third who stopped a lot of hot grounders with his chest. The player manager was Frankie Frisch, the Fordham Flash who played second. Joe “Ducky” Medwick played the outfield with more verve than grace and once ran through an outfield fence trying to catch a fly ball. Their two best pitchers were the Dean brothers, Dizzy and Paul. Dizzy lived up to his name and earned a reputation which lives to this day.

In the late 30s, a group of the Gas House Gang put together a stage show traveling through the Midwest, capitalizing on their reputations for goofiness. My father took me to see the show when it reached Dayton. They told corny jokes and stories, played “musical” instruments like the wash tub base and “sang”. My father was a little disappointed because they used the word “hell” a lot which in the 30s was pushing the envelope a bit, even for a cosmopolitan city like Dayton, Ohio.

Oh man – I haven’t laughed this good in ages. This may very well be one the funniest things I’ve ever read in my life. Just plugged it over on my Texas Rangers site:

http://www.rangerfans.com/archives/2007/02/baseball_bugs.html

I signed up at this site just so I could say how much I enjoyed that post. And I agree with Joe Siegler… may be the funniest thing I’ve ever read. Brilliant. I kinda wish you had gone into the wormhole theory a bit more, but I’ll take it as is. Thanks for a good laugh.

I registered as well solely for the purpose of leaving a comment.

This is an absolutely brilliant, innovative, inspired piece of work. The premise was fantastic alone; the fact that you maintained the deadpan scholarly humor throughout such a long piece is quite a feat. This is a gem the likes of which I’ve never seen … anywhere.

Keep writing. You’ve got a gift, my friend.

Scott

Wow, this was found on the second page of google searching for bugs bunny.

The way this season is going to find such a humorous, eloquent gem is a gift, thank you. I’m donating to your site immediately, please keep up the effort, it’s appreciated more than words can say.

I realize this comment is a bit late, but I think an incorrect assumption may have been made regarding the analysis of the accelerated ball after Bunny’s pitch.

The thought was that Bunny had thrown a ball with deceiving slowness and then somehow accelerated it, through vocal compulsion. Since this introduces either new concepts in physics or a proof of psychokinesis in a scale never before seen I must state great concern for its validity. I present a third option as to yet unexplored, which, while still grand, does not introduce any special physics.

Since we do not see the actual trajectory of the ball from release to catch we do not have to make assumptions as to its path. For this reason I conjecture that the ball did not follow a traditional “straight line” trajectory. Instead, because of the Magnus effect imparted by extreme upwards spin on the ball, it looped upward and around on the way to the plate. A large enough looping trajectory would allow time for Bunny to move into position, and also preserve much of the imparted energy on approach to the plate because of gravitational acceleration. It also has the benefit for allowing the pitch to appear “straight” when crossing the plate since angular momentum would eventually lessen to the point where gravity equals/defeats any airflow pressure differences.

I don’t know if this counts as an homage, but Art Thiel, writing today on the Manny Ramirez suspension: “The drug-testing program actually caught a prominent player during a season and pulled the trigger, which always seemed as likely as Yosemite Sam actually blowing Bugs Bunny to smithereens.”

I just have to say that this is f-ing brilliant. I own the copy of that year’s Best Sportswriting book (actually, I own all years except for the last couple, which I’ll buy as soon as I see them used or cheap somewhere), and it’s amazing that something on the Internet made it into a very prestigious collection (they evaluate hundreds and hundreds of entries every year before narrowing it down to about 20, as explained in their introduction). They also have a famous writer as the guest editor every year, who helps evaluate the entries.

Well done, DMZ! You make USSM readers very proud.

You have combined two of the great passions of my life–baseball and Bugs–in what may be the greatest blog post I have ever read. Brilliant, sir, absolutely brilliant!