You’re Fired, Probably

If ever you’d care to lose faith in all of humanity all at once — or, at least the middle- to upper-middle class, American portion of humanity — you’d do well simply to point your web browser to nytimes.com, direct your gaze towards the bottom right of the screen there, and behold the most popular articles of the day.

Invariably, your worst fears about the species — that we’re petty, self-obsessed — will be realized. Data show that a full 60-65% of these articles are about which kindergarten will best prepare your unborn child for Harvard; another 20% or so concern the health and beauty habits of French women (spoiler alert: they’re anorexic!); and the remainder are just borderline-pornographic descriptions of something called quinoa.

In short, it’s harrowing.

There are exceptions, though, and one such has occurred this week, as the story of Steve Slater, and his spirited departure from a twenty-year career as a flight attendant, has garnered a great deal of interest from the Times readership and, more generally, the American public.

If you’re not familiar with how Slater took care of bidness, here’s a brief account from the very popular Times article:

After a dispute with a passenger who stood to fetch luggage too soon on a full flight just in from Pittsburgh, Mr. Slater, 38 and a career flight attendant, got on the public-address intercom and let loose a string of invective.

Then, the authorities said, he pulled the lever that activates the emergency-evacuation chute and slid down, making a dramatic exit not only from the plane but, one imagines, also from his airline career.

On his way out the door, he paused to grab a beer from the beverage cart. Then he ran to the employee parking lot and drove off, the authorities said.

If you’re on the Twitters or are a reader of the disgustingly well-written Walkoff Walk, then you’re probably aware of this Giant News Event. Though some old-codger types might balk at Slater’s antics, I think most of us have found ourselves in such a situation as we would gladly inform our bosses, co-workers, customers — anybody, really — where they might stick it and how hard.

Plus, the fact that he had the presence of mind to take a beer with him kinda makes this Slater character an all-star in everybody’s

Slater’s dramatic exit — and the public’s corresponding fascination with it — is relevant to USSM readers not only insofar as it’s totally awesome, but also because the events unfolded on the same day — and, really, almost at the same time (mid-day-ish) — as Don Wakamatsu’s considerably less hysterical and certainly less surprising departure from that great, offensively challenged airplane known as the Seattle Mariners.

I don’t know exactly what’s to be learned from these twin events, but the fact that they occurred almost simultaneously and that both represent instances of someone leaving his place of employment in a conspicuous manner — well, it seems to beg for some kind of comparison.

If anything, probably what we can learn is just how weird baseball managing is in the grand scheme of possible employment. Like, here are some of the jobs that my friends and family currently hold: lawyer, writing instructor, sitcom staff writer, other kind of lawyer, children’s librarian, baseball writer, advertising copy writer, computer programmer, third type of lawyer. (Note to self: meet other people besides lawyers.)

With the exception of the comedy writer, whose job is largely dependent on a network’s decision to pick up the relevant sitcom, all these people have one thing in common: mostly decent job security. In each of these cases, the likelihood of getting fired because of poor performance is pretty close to nil. Any of these people would have to reallyreallyreally eff up in order to be relieved of their duties.

Nor is that to say that this particular sample of the employed is super-good at their respective jobs. I mean, they’re probably all good. But even if they weren’t, it’d probably be easy enough to hide their shortcomings.

In baseball, though, managers are fired all the time. And they have almost no job security. And, because we have no sure way to judge a manager’s actual contribution to wins/losses, he can be fired — usually is fired — for circumstances entirely outside his control.

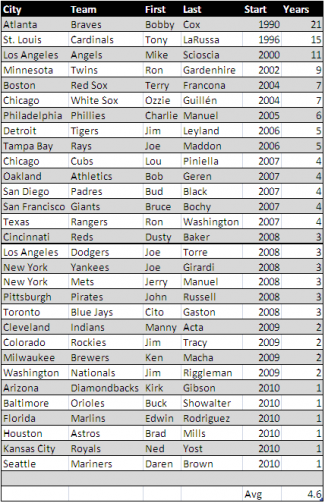

Consider this list of the thirty current managers, sorted by years as manager of their respective teams.

What jumps out first from this list is that a full six of those men weren’t managers at the beginning of the season. That means, right off the bat, that 20% of the employees from this particular group were fired just this year. Consider, by way of comparison, if Morrison & Foerster (the New York-based law firm known affectionately as MoFo) were to fire 20% of its associates. People would, in the parlance of today’s youth, freak the eff out.

Here’s what else we see: that the average manager can expect about 4.5 years of employment. But even that number is probably on the high side when we consider that (a) we’re rounding all the mid-year hires up and (b) the median number on that list is actually three years.

Three years? That’s crazy.

Let’s try a thought experiment. Say I’m a dude who can offer you a job. And say this job is pretty hot. But here’s the thing about it: you’re probably gonna be fired in 2013.

Would you take it?

If the men who’re employed as major leage managers are any indication, the answer is probably “yes” — because those are essentially the terms to which they’re agreeing when they sign their managerial contracts. Now, of course, there are quite a few managers who’re on their second or third or — in the case of Lou Piniella — five teams, which might skew the numbers upwards. Moreover, if someone’s managed for a major league team, he very likely will catch on at a lower level.

Perhaps it’s for these latter couple reasons that little drama surrounds managerial replacements. With the exception of former Seattle manager Mike Hargrove’s bizarre mid-season departure in 2007 — with the team standing at 45-33 and in the midst of an eight-game winning streak — there’ve been very few memorable managerial departures of late. (And there certainly haven’t been any involving emergency slides.) Perhaps managers know they’ll find employment elsewhere, if in a slightly less glamorous league. Perhaps, because many of them are ex-players, they understand that baseball is a game defined much more by failure than success.

Whatever the case may be, the principal draw of baseball’s managerial positions certainly isn’t job security.

Thanks to Dave Cameron and Zach Sanders for their help with Mike Hargrove info.